While the writer possesses a good part of the pieces of the mosaic inherent to the handing down and the perpetuation of his own specific initiatory tradition, the Eleusinian tradition of the Mother Rite, I recognize in all humility, despite decades of studies and research, that I only possess a few fragmentary pieces regarding the karst path through which the “Daughter” Rites of Eleusinity have reached our times, primarily the Samotracian and the Orphic ones. And the same applies to realities which, despite belonging to the Tradition and the line of transmission of the Mother Eleusinity, were separated from the diaspora and continued their path in isolation. I am referring specifically to some of the dispersed tribes of Eleusis, whose descendants, present today not only in Italy, but also in other European countries and overseas, have already shown in the past that they refuse honest dialogue. Today I hope will read these lines.

Beyond the Daughter and Pythagorean strands, and the complex reality determined by the dispersion, within the Mother Eleusinity, of some of the primary Tribes of Eleusis, certainly not negligible fragments of the Tradition have also survived, in Italy and elsewhere, in the within small groups of families. A fitting example in this regard is provided by Roberto Sestito in his essay “History of the Italian Philosophical Rite”[1], when he talks to us about the Phratries.

The reference context to which Sestito refers, that of the precursors of Neapolitan “Egyptian” Freemasonry, could apparently go beyond our discussion, but we will see that this is not the case. The author highlights, that the founders of Freemasonry of Naples in the 19th century, in their “Historical Prolegomena to the Constitutions of the Scottish Rite” published in 1820 (which are most likely nothing more than the transcription of the 1750 Constitutions of the Prince of Sansevero Raimondo Di Sangro) are explicitly linked to a “regional” tradition of Southern Italy, a tradition expressly of a “Pythagorean” character, and which a descendant of the Count of Clavel, owner of a villa in Anacapri (place where the Count, after the First World War, used to spend long periods of the year in the company of Amedeo Rocco Armentano and Italo Tavolato) claimed to have known that the covered degrees of the Mizraimite Rite had never left Naples, representing for our peninsula a sort of «sacred pledge»[2]. And also, that, in the Annals of the Italian Philosophical Rite, in relation to the Rite of Mizraìm and the related Supreme Council for France, there is talk of a «Calabrian Constitution»[3].

As Sestito highlights, the term Calabrian Constitution would hide a precise philosophical allegory, like the Egyptian rite, regardless of the pure and simple geographical reference, because, as Giustiniano Lebano wrote in one of his articles, “The entry “Egypt” in arcane does not it was intended for that commonly known geographical place. The entry “Egypt” is the primary category of Aig-Ipt-Os. Having explained the various entries with hermeneutics, each Arcane Urbe was understood to be connected to the vast band of the urban zodiac of the arcane universe. Egypt therefore is an arcane voice that explains the arcane World. And the Egyptians were called the Subconstituted“[4].

It would seem that in Naples, in the first half of the 18th century, an initiatory current came (or re-emerged) to light which, with its own criteria, and did establish itself in the high degrees of the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry and among the leaders of other esoteric orders of a Hermetic, Egyptian and Templar nature. In short, “a superb spiritual renaissance not limited only to Freemasonry and not dissimilar to other flourishings that occurred in other eras and with somewhat similar purposes“[5].

Tiziano Vecellio: Allegory of the Three Ages of Man, ca. 1570, actually depicting an initiatory concept of the cult of Serapis (London, National Gallery)

The treasure chest that preserved such a precious seed was probably kept in the environment of the Phratries, mysterious associations typical of Southern Italy, whose bonds of solidarity were always very close and resistant, due to customs and mentality, to all innovations of a social and religious nature and which have been perpetuated over time without the need for statutes or written regulations.

The Phratry, in the interpretation given to us by Sestitus, was a partnership, derived from the ancient model, we could easily say from the Greek γένος (ghenos), which crossed and transcended the model of the traditional family, normally very closed, to open up to certain individuals even of different social levels or other geographical locations, and was formed when faced with the need to maintain and transmit a secret, occult knowledge or a wealth of traditions and knowledge destined to remain the prerogative of a few and not to become the public domain or the object of an extended sharing. A concept which can find similarity in the Scottish model clan, or in that of tribes (think of the sacred tribes of Eleusis), real extended families whose existence and actions were based on the defense and the handing down of a tradition.

In his essay, Sestitus clearly refers to a transmission of initiatory Knowledge and certain ancient mystery Traditions that occurred in Southern Italy, but it was in reality a geographically much more widespread phenomenon and, in many aspects and various forms, extendable to the the entire European continent, even if the Italian peninsula unquestionably represented, for a whole series of more or less well-known reasons, the fulcrum of this phenomenon. But the example called into question by Sestito is more than apt and explanatory for the purposes of understanding the dynamics of such a complex phenomenon and, at the same time, impenetrably inaccessible to most.

In fact, as various sources confirm, it is precisely thanks to the work of something very similar to the Phratries that the Mystery Tradition has managed to survive, both in Italy and in other European nations, with an uninterrupted thread, from antiquity up to today. Both the Mother Eleusinian s and those of other Orders and Rites know this very well, because, regardless of the parallel survival of the ecclesial institutions hidden within the Neoplatonic Schools, the Academies and other similar structures, the majority of the mysterious heritage and Eleusinian wisdom survived within groups of families, which could or could not be in contact with each other (but which for many centuries preferred not to be), families which could also be or become of an extended nature, on the model of the clan, of the tribe or phratry, should the need arise (for example, in the case of the lack of a direct heir by bloodline, resorting to adoptions of trusted people or marriages planned for this purpose). Families in which the passing down of wisdom and initiatory knowledge often took place according to an unwritten rule but motivated by a whole series of security reasons: that of the generational leap, with the passage – for example – from grandfather to grandson. And many of these families have coincided, in history, with important dynasties, noble houses and lordships, as in the case of the Medicis, the Gonzagas, the Estes, the Viscontis, the Da Varanos, the Da Montones or the Malatestas.

Piero Della Francesca: Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta in prayer before Saint Sigismund, 1541. It actually depicts the initiation rite of Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta into the Pythagorean Order, officiated by Giorgio Gemisto Pletone (Rimini, Tempio Malatestiano)

Below I report the text of another interesting secret manuscript document dating back to the 19th century, acquired and preserved to this day by the Scuola Eleusina Madre of Florence. Although it was the subject of some form of censorship which omitted the names contained in it, replacing them with dotted initials, it is very clear and explanatory:

“In some family lines, it seems that some “legends” have been handed down from father to son or from grandfather to grandson, we don’t know what else to call them, through which it was possible to reconstruct a legacy that had disappeared in the eyes of most (… ). It is known, for example, that the Count of V., who lived in 18th-century Lorraine, managed to collect a large mass of certain information from other families, which he added to those already in his possession, handed down to him by his ancestors in the castle of F. Information that allowed him to create twelve volumes of six hundred pages each. But the Count of V. was well aware of having collected only the hundredth part of a certain secret tradition. He was not the only one, in modern times, to possess a secret body of literature. It was said, for example, that the collection of the Count of S.G. was colossal and that G.C., a well-known figure in literature, owned a similar one. Another, certainly, was in the hands of the Kings of F.

If we could bring together this underground knowledge, we could certainly come up with something sensational, but every family, club or school has always been rigorously jealous of its own cultural heritage, always ready to take what is missing from its knowledge without granting anything in exchange.

It seems that these notions, which have come down through the centuries, are the same ones with which the Etruscan poets were concerned, who were all of the Eleusinian school, and so the Proto-Eleusinians of the Kureta Order of the Cretan Rite, the very secret circles of the Orphic Eleusinians, of the Samothracian Eleusinians, the Pythagorean Eleusinians, the Eleusinians of the Egyptian Rite, of the Roman Rite, etc., as well as the selective School of the Mother Eleusinians and the very secret Circle of the priests of the God Ampu, into which some Platonists were also accepted late in life. All these would have learned the knowledge, or rather the archaic-erudite discipline, from the Minoans- Lelegians, or those Pelasgian populations scattered in the Aegean and Anatolia. Populations that considered themselves heirs of the last Atlanteans.

If this is true, it is nevertheless surprising how these notions, oral and mysterious or contained in very secret writings, have resisted the wear and tear of the centuries, even more so if we consider the fact that they were passed down by very few chosen people. Here we are touching on an order of ideas that is difficult for most people to understand.”

Those who well know the Italian esoteric history of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries should know what the real function was of most of the numerous cultural, scientific and literary academies that at that time flourished and developed in many cities of the Peninsula. An academy is, by definition, an institution intended for the most refined studies and for the deepening and advancement of knowledge of the highest level, both in the sector of scientific research (Astronomy, Medicine, Natural Sciences) and in the field of Philosophy. , of Literature or of the Arts. The aura of prestige associated with the origin of the name of this type of institution, especially starting from the 15th century, pushed many institutions, generally set up by private individuals and with the direct intervention of important figures or patrons , to boast of this name. The term Academy, in fact, famously derives from Greek and can be traced back to the famous philosophical school of Plato, founded in Athens in 387 BC. and located in a place just outside the city walls, on land donated by the war hero Academo. But few today remember that – as we have just mentioned – it was precisely thanks to the academies that, at the end of the 4th century AD, the majority of the religious and mystery institutions of antiquity, persecuted by the Christianity now dominant in Rome and throughout the Empire found safe refuge and continuity, entering a phase of forced clandestineness which allowed its perpetuation. Starting precisely from the Eleusinian ecclesial and priestly institutions, which took refuge, from 380 AD, after the closure of the Mother Sanctuary of Eleusis, within the safe walls of the Platonic Academy of Athens, re-founded we could say specifically for this purpose by the philosopher Plutarch of Athens, who was the grandson and heir of the last Pritan of the Hierophants of Eleusinity, Nestorius the Great.

In the same way and within similar institutions, the institutions of the Pythagorean Order, the Isiac priestly colleges and the cult of Serapis and other important initiatory realities of the pre-Christian Mediterranean survived and were perpetuated.

Marsilio Ficino, Cristoforo Landino and Agnolo Poliziano, all three Eleusinian initiates of the Orphic Rite, in a detail of Domenico Ghirlandaio’s fresco Apparition of the Angel to Zaccaria (Florence, Santa Maria Novella, Tornabuoni Chapel)

The birth of “modern” Academies, starting from the one founded in Florence by Cosimo de’ Medici and Gemisto Pletone and then led by Ficino (but we could list many others) is closely linked to the development of Humanism and the rediscovery of ancient Philosophy, in particular the Platonic one, as well as the greatest expressions of classical civilization. In fact, the universities, although already widely spread in many Italian cities, with rare exceptions had remained closely linked to the doctrine of the Church and based on the limiting and flawed Aristotelian Scholasticism.

That is why the Humanists (many of whom were first and foremost Initiates) created alternative institutions where they could cultivate their own model of culture, namely the Academies. But, I also explained how there was much more. Just as Humanism in itself was essentially the product of ancient pre-Christian mystery and initiatory traditions that survived like a karst river through the centuries of the Middle Ages and reappeared with vigor on the scene from the beginning of the 15th century, many of the Academies that developed in Italy from the 15th century onwards, no more and no less than what had happened a millennium earlier with the neo- Platonic academies in Greece, Egypt, Syria and other provinces of the Roman Empire. They were a refuge and a “profane” façade ” of those same tenacious initiatory traditions. So much so that, behind the “facade” of the study of philosophy, literary or musical production and scientific research, within these institutions, at higher levels not immediately accessible to the layman, secret initiatory teachings and real initiatory practices and rituals of strands of the Eleusian Mystery Tradition (both in its “Mother” and “Daughter” expressions, such as the Orphic and the Samotracian), of the Pythagorean or the Hermetic one, happened. And this phenomenon intensified more in the second half of the 16th and 17th centuries, due to the Counter-Reformation and the resurgence of the Inquisition. The golden age of Renaissance was now over. The Church had begun to tighten its grip against heresies and its enemies, both internal and external. The numerous circles of initiates, especially those operating in the territories nominally subject to the Papal State, had to move with ever greater circumspection at that time and the use of certain cultural institutions, some of which enjoyed the formal protection of Bishops and high prelates, became more necessary than ever.

For example, very few know that even the historic Accademia dei Lincei, which still exists today, arose in the same context we are talking about and was founded by Federico Cesi, Duke of Acquasparta and Grand Master of the Pythagorean Order.

A similar discussion could be addressed – and we will certainly do so, even if elsewhere – for the majority of the numerous Academies that flourished on Italian territory between the 15th and 16th centuries, not only those with a markedly Platonic orientation, but also those both scientific-naturalistic and artistic and literary, Arcadia first and foremost. All institutions which, behind the profane façade of cenacles dedicated to culture, literature, poetry or the arts, hid precise initiatory paths of a mysterious nature at a higher level.

This is not the place where to exhaustively address the history and development of these Academies, but it is still worth making some observations regarding the events that led to the conception and birth of what was undoubtedly one of them the most famous and at the same time the most mythical: the Florentine Platonic Academy, one of the most important philosophical and initiatory realities of Renaissance.

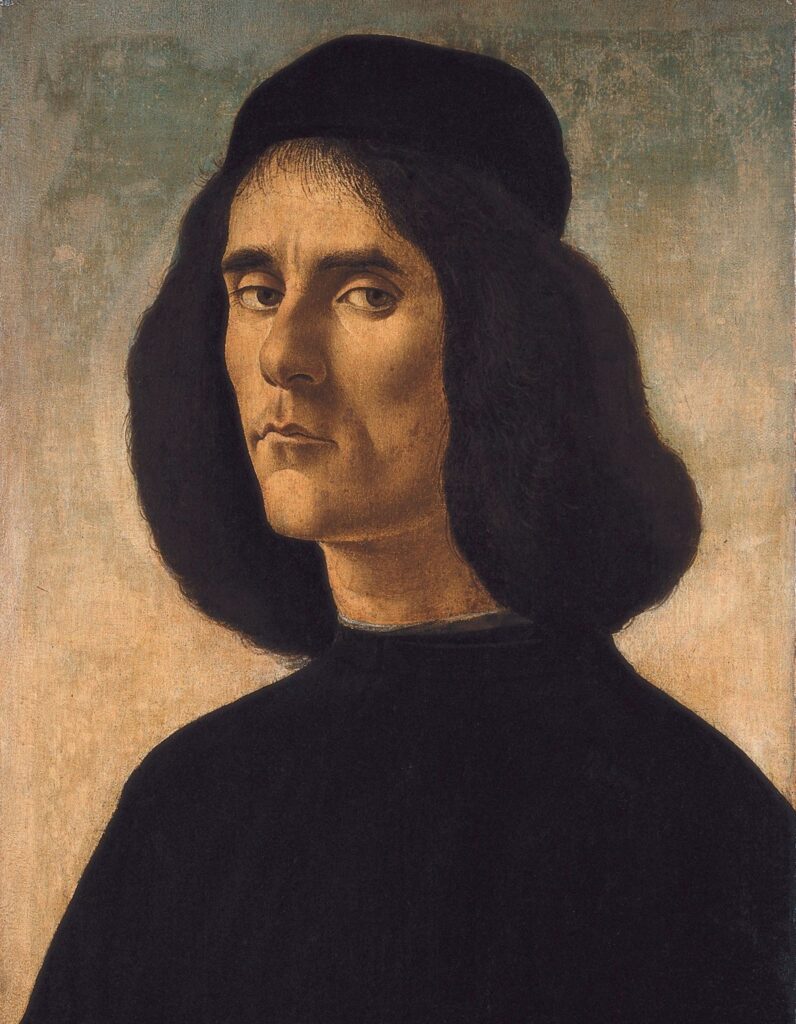

Marsilio Ficino, born in Figline in 1433, son of the personal doctor of Cosimo de’ Medici and Alessandra di Nannocchio di Montevarchi (but most likely the secret son of Cosimo himself), was one of the greatest philosophers and initiates of Renaissance and one of the characters, in the Medicis’ entourage, who contributed most to the rediscovery and reinterpretation of Platonism and ancient mystery. Moreover, these words of his are famous: «Ego sacerdos minimus, I had two fathers, Ficinum medicum et Cosmum Medicem. From the first I was born, from the second I was reborn. The first entrusted me to Galen, doctor and Platonist, the second consecrated me to the divine Plato. Both destined me to medicine. In fact, if Galen is the doctor of bodies, Plato is the doctor of souls.”

As Paolo Aldo Rossi wrote in one of his interesting articles[6], if his date of birth is 19 October 1433, that of his rebirth (i.e. his initiation) is 1462. And, in that fateful year, Marsilio received from Cosimo two gifts: a precious Platonic codex and a villa in Careggi so that he could dedicate himself more easily to the translation of Plato; these events destined him, according to him, to the realization of that dream that the Medici prince had developed during the stay of the Greeks in Florence, on the occasion of the Ecumenical Council of 1439, a council in which he took part, as lay advisor to the Emperor Byzantine John VIII Palaeologus, George Gemistus Plethon, one of the greatest philosophers of the time and Grand Master of the Pythagorean Order. Ideally, this date marks the birth of the Florentine Platonic Academy, an association of philosopher-initiates directed and coordinated by Ficino himself in the name and on behalf of the Medici family. And it also indicates the beginning of his fervent season of official activity as a translator from Greek, as a commentator on Platonic philosophical literature and as a true Orphic-Platonic mystagogue at the service of Tradition and the renovatio of the Pious Philosophia.

Since his first studies, the young Marsilio felt so attracted by Platonic philosophy that Antonino Pierozzi, archbishop of Florence, later canonized and proclaimed patron of the diocese of Florence by Pope Roncalli together with Saint Zanobi (in reality a Pythagorean initiate and an unscrupulous fanatic), intervened on several occasions to his father Diotifeci, suggesting him to send his son to Bologna to study medicine so that he would not progress further on a philosophical path that could lead him to heresy. Despite these pressures, the young man, in addition to studying Medicine in Bologna, was also educated in the humanistic studies in Pisa and Florence, having as his first teacher of Philosophy Nicolò Tignosi da Foligno, an Aristotelian doctor with clear Thomist sympathies.

But Marsilio’s interest was immediately focused on Epicureanism (his first love was for Lucretius who he would renounce in his mature years) and then, with an overwhelming passion that would fill his life, on the thought of the Athenian philosopher which he would always call Plato Noster.

Sandro Botticelli: Portrait of Michele Marullo Tarcaniota, 1497 (Guardans-Cambó Collection of Barcelona. On loan to the Prado Museum, Madrid)

(Collezione Guardans-Cambó di Barcellona. Esposto in prestito al Museo del Prado, Madrid)

In “The Proem to the Epitomes, Arguments, Comments and Annotations in Plotinus”, dedicated to the Magnanimous Lorenzo de’ Medici, Savior of the Fatherland”, Ficino wrote verbatim:

“The great Cosimo, Father of the Fatherland by public decree, when the Council for the unification of the Greek and Latin Church was taking place in Florence under the pontificate of Eugene, often listened to the discussions on the Platonic Mysteries of a Greek philosopher whose name was he called Gemisto and his nickname Pletho, almost as if he were a second Plato. And he was so inspired by the ardor of his words that he was led to dream in his lofty mind of an Academy that he would create as soon as the opportunity was given. Then, while that great Medici was still giving birth to this conception, he assigned me, son of his illustrious doctor Ficinio, still a child, to this task. He dedicated himself to this day after day. He also made sure that I had all the Greek books, not only by Plato, but also by Plotinus.”

A fundamental first-hand testimony, this one from Marsilio Ficino, which attests not only to the circumstances and the moment in which the Florentine Platonic Academy was conceived, but also to the fact that, in the intentions of the Pater Patriae Cosimo it would have been up to him (who in the 1439 was a child of just six years!) the honor and the burden of directing it.

It is my belief that the choice of the still infant Marsilio, by Cosimo with the probable approval of Giorgio Gemisto Pletone, as the future leader of the Academy was anything but random and that it derived from a precise astrological calculation. Somehow those two key figures of Renaissance must have seen, in the child’s birth chart, a life devoted to Knowledge and Wisdom and, consequently, in him the most suitable person to play such a role. And, in fact, from that moment on, Marsilio was educated and prepared for this future task.

Having returned from two years of studies in Bologna (1457-1459), and since Archbishop Antonino Pierozzi had died in the meantime (who in Florence represented a Pythagorean initiatory faction fundamentally hostile to Medicean Orphism and Platonism), Marsilio was able to dedicate himself again to his favorite themes, also thanks to the fact that it was Cosimo the Elder himself who not only cleared his way of any impediment, but even favored him with all the means that a Lord could offer to a courtier-literate. As Paolo Aldo Rossi always observes[7], in the relationship between Cosimo and Ficino two new figures emerge: that of the “Lord” who personally participates in the research and is sincerely interested in the contemplative outcomes of Platonic theology rather than in the active ones of ethics and of Aristotelian-scholastic political philosophy, and that of the philosopher-courtier who is professionally entrusted with the task of intellectual of the regime. Marsilio is protected from ecclesiastical censorship, he is assured excellent living conditions and is given ample means to carry out his studies and duties. In exchange, nothing is asked of him other than political loyalty, prompt and unconditional adherence to the patron’s requests and productive efficiency such as to guarantee constant intellectual prestige to the cultural institutions of the court.

But what Rossi does not explain well is that the Medicis had not a mere political project for Florence, but rather an initiatory-political-humanistic- philosophical project of wide scope and great ambition. A project which, in their intentions, was to truly transform the City of the Lily into a new Athens, within the framework of a renewed Italy, in which the altars of the Immortal Gods would also be restored.

In any case, Ficino’s passion for Platonic Philosophy and for the Orphic- Eleusinian mystery must be considered completely sincere and not induced by contingent conveniences, just as Cosimo’s is equally univocal and overwhelming.

Before 1462, Marsilio had translated, «mihi solo» (“for his personal use”, in reality for the exclusive use of a restricted initiatory circle and absolutely not for publication), the hymns of Orpheus, Homer, Proclus and Theology of Hesiod, coincidentally, among all the classical literature available at that time, was precisely a set of fundamental texts for the Orphic-Eleusinian Mystery Tradition. And, when in 1462, he set about translating the entire Platonic work, now completely available, an event occurred that was destined to radically modify a significant part of the history of Western culture of the following two centuries: the rediscovery of the corpus of emetic texts. In that year, the monk Leonardo da Pistoia, one of the “messengers of light” that Cosimo had sent to the East to recover the lost treasures of Greek literature, brought back from Macedonia a copy of the “Corpus Hermeticum” (a manuscript containing the first fourteen books of a the work which was now mythical and which had been fabled throughout the Middle Ages. Cosimo was so fascinated by it that he ordered Marsilio to immediately interrupt the Platonic translation and immediately begin that of Hermes: “…he commissioned me to first translate and comment on the Trismegistus and therefore Plato”, Ficino reminds Lorenzo the Magnificent in the Dedication of his “Commentary to Plotinus”.

This translation was finished before April 1463. Such speed of execution depended both on the fact that Cosimo, now very old, hoped he would be given the time to read it, and because the translator, convinced that he had got his hands on the fons et origo of Western wisdom, had dedicated all his energies. In the same year, Tommaso Benci edited Ficino’s Latin translation into the vernacular, which would only definitively be printed in 1471.

The Florentine Platonic Academy came true according to the planned plans and not only was it an irrefutable reality, but it also became for many years a fundamental point of reference for philosophers, initiates and scholars from other Italian regions and other European nations. Through him, profitable exchange relationships had been established with similar institutions, both in Italy and abroad. Yet, many modern historians, starting from the 19th century, have inconceivably gone so far as to deny or question its existence. Thus, for example, did the historian Gustavo Uzielli, who, first in the work “The Life and Times of Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli (1894)”, and then in “The Journal of Erudition (vol. V, 1897, nos. 15-21)”, in the essay “The True and the False Renaissance” and, in other minor writings, he never missed an opportunity to argue that “The Platonic Academy is a fairy tale”. Yet Uzielli, a historian far from being ignorant of esoteric and initiatory themes, would have had sufficient elements in his hands to affirm the exact opposite. And he certainly wasn’t the only one, so much so that even today one of the favorite sports of many frustrated academics in search of visibility is to target the Flotentine Platonic Academy and to deny outright that it ever existed.

Here, objectively, we go far beyond omissions or historical reticence. We are obviously dealing with academics who passively apply team orders dictated by obscure creators of paradigms.

In another essay of mine to be published soon, “From Eleusis to Washington D.C.”, I explained how, as evidence of the fact that in the level of reality perceived by the vast majority of the population – often completely unaware of the complex power games that have always been in place for the control of the destinies of the world – nothing is ever as it seems, it has not been uncommon in History that ancient mystery and initiatory Traditions, adverse to Christianity, have infiltrated and prospered within the Church. And this happened not only in the monastic orders, natural refuge in the Middle Ages for many initiatory realities, including non-Christian ones (which in the silence of the cloisters, cells and, above all, libraries, were able to transmit their initiatory and wisdom heritage for a long time undisturbed), but even in the highest ecclesiastical hierarchies, up to the Throne of Peter itself.

This should not be surprising. The Holy Roman Church has always been seen by certain entities, which have been ferociously persecuted since its inception, as a sort of large “container” within which they could secretly operate decidedly better and in greater security than in blatantly and outside of it. We could cite numerous cases in this regard: from the secret circles of the Orphic Eleusinians within the Camaldolese Order, and in particular in their Florentine “branch” of Santa Maria degli Angeli, up to those of the Pythagorean Eleusinians within the famous monastery of Saint Dié des Vosges, where in 1507 great Initiates such as Martin Waldseemüller and Matthias Ringmann decided to make public a fundamental truth about the “discovery” of the New Continent. But this is another story…, which we will return to in appropriate contexts.

Starting from the 4th century AD, and especially after the promulgation in 380, by Theodosius and Gratian, of the infamous Edict of Thessalonica which imposed Christianity as the only religion, effectively prohibiting all the others from continuing to exist, good part of the then known world was preparing to fall into an absolutely unprecedented grip of single, exclusive and darkening thought, and to slide under a heavy cloak of intolerance and persecution. From Theodosius onwards, everything that was attributable to traditional religiosity and spirituality, from works of art to sacred architecture, from philosophy to literature, up to the simple expressions of ancient popular religiosity, was derogatorily branded as “pagan” and fact prohibited, destroyed, subjected to censorship and damnatio memoriae.

As we have already mentioned, with the outbreak, from Constantine onwards, of Christian persecutions against all the traditional cults of the Roman Empire, with the burning of libraries and the demolition of the sacred Temples, the loss of the cultural and religious heritage of the Greco- Roman classicism was truly immense, incalculable, and it has been estimated that only a minimal part of ancient literature survived and has been preserved, including that of a scientific and religious nature.

The Eleusinian ecclesial institutions and the related mystery schools – holders and bearers not only of an ancient spiritual tradition, but also of a clearly matriarchal vision of society and of the most genuine expression of the “Sacred Feminine” -, after their closure, in 380 AD, of the Mother Sanctuary of Eleusis by the last Pritan of the Hierophants officially in office, Nestorius the Great, were actually transferred to the Platonic Academy of Athens, founded at the same time as the closure of the Sanctuary by the Neoplatonic philosopher Plutarch of Athens, who was Nestorius’ nephew and from whom he had inherited both the knowledge and the sacred title. The Athenian academic institution therefore represented a safe haven for the Eleusinians and their mystery schools at least until the time of Justinian, and when, by decree of the latter, the Academy was formally suppressed, safe protections and seats were ready alternatives.

A similar path was also undertaken by the Pythagorean Order, even if it had long since distanced itself from the Mother Eleusinity for political and doctrinal reasons, no longer recognizing the superior authority of Eleusis for some centuries. The great French Initiate Jean Marie Ragon, who lived between the 18th and 19th centuries, who, in addition to being a Freemason was also an Eleusinian, left us in-depth documentation regarding the survival of this Order, from the times of Justinian (6th century) until the 19th century, throughout the Middle Ages, the Renaissance and the Modern Age.

Some of these realities even went underground in a manner agreed with the Church itself. This should not be surprising at all, because those Bishops who in fact, after the Edict of Thessalonica and its implementing decrees, fully managed the reins and fate of the Empire were at that point interested in presenting themselves in the eyes of the masses as absolute triumphants over the “paganism” in order to then dedicate themselves to consolidating their own power and fighting against their own numerous internal “heresies”.

And, naturally, above all to what was one of their primary objectives: the fight against Johannite Christianity, which “Paulism” had effectively usurped, and which continued in a karstic way to prosper in many regions of Europe and the Near East, under the protective wing of important power families who would definitely assume a leading role in the following centuries, leading to the consolidation of Cathar power in Southern France and the birth of the Templar Order. Therefore, agreeing with the Eleusinians, the Pythagoreans and other initiatory and mysterious realities on a tacit and certain entry into clandestinity in exchange for a “formal” surrender represented at that time for the Church a sort of exit strategy from a situation of impasse with no more concrete outlets. Certain realities, in fact, were too consolidated, powerful and ramified and still in some ways protected by important fringes of political power (particularly in the Senate) to be canceled by a simple imperial edict, even if reiterated several times. By coming to terms with them, the Church effectively saved its own power and at the same time found itself free to face other “enemies”.

Certain secret agreements did not imply a total cessation of persecutions. And the followers of the Eleusinian, Orphic, Pythagorean and Isiac Orders had to double watch their backs, intensify precautions and security measures to survive conspiracies and targeted murders or easy accusations of “heresy”. The agreements which I am referring to guaranteed to these realities a wide freedom and autonomy within Academies founded ad hoc, in exchange for a formal closure of the Temples and their disappearance from the public scene, but they were still unwritten agreements and which both the Church and the imperial authorities often disregarded under various pretexts, generating heavy tensions and retaliations.

Many of these initiatory realities, paradoxically (but not so much), mostly in the Carolingian age, infiltrated the Church itself, taking note of how much easier and easier it was to survive and secretly perpetuate their own traditions and ideas within it rather than outside. And they did so by strategically favoring – as we have already mentioned – some monastic orders, where they would have had access to libraries (no small feat in those dark centuries) and where they created numerous secret circles which consolidated over time, becoming real own “control rooms” of political events.

However, the Church did not take long to tighten its limits and act decisively towards everything that could call into question its power, especially temporal power. Moreover, its very survival was at stake, as it had for some time now found itself under the crossfire of tenacious mystery traditions that wished to overthrow it, thus consuming their centuries-old revenge, and of an increasingly powerful Johannite Christianity which, under the impulse of the now very powerful Order of the Pauperes Commilitones Christi Templique Salomonis (better known as the Knights Templar), aimed to do the same. Thus, in 1198, by Pope Innocent III, the establishment in France (where the Cathar threat was now becoming unsustainable) of a special ecclesiastical tribunal whose declared aim was to fight – and above all suppress – everything what the Vatican considered, both generically and indiscriminately, “heresy”. Thus was formally born what sadly went down in history as the Holy Inquisition, a reality that progressively extended throughout Europe by Pope Gregory IXth, with the institution of permanent and territorial inquisitors, chosen and selected within the orders of the Franciscans and of the Dominicans, the only ones whom the ecclesiastical hierarchies still trusted.

Agnolo Bronzino: Portrait of Cosimo I De’ Medici in the guise of Orpheus, 1539

(Philadelphia, Philadelphia Museum of Art)

The mystery and initiatory Traditions of antiquity, that survived the Christian persecutions and went underground towards the end of the 4th century AD, during the Middle Ages and in Renaissance, after having decided several times to re-emerge, were forced to do so within the context of a society now strongly Christianized and dominated by the single thought imposed by the Papacy. Certain affirmations of identity and belonging, especially if expressed in works of art and architecture, constituted precise messages addressed by initiates to other initiates – that is, to those who possessed the correct interpretation keys to understand and receive them – and therefore had to necessarily be disguised with particular symbols and allegories. There wasn’t much to joke about, because certain statements could constantly jeopardize the very lives of both the executors and the clients. It was extremely easy, in fact, to fall into the trap of the Church and the Inquisition, which was in fact already operational starting from 1184, with the issuing of the bull “Ad Abolendam Diversarum Haeresum Pravitatem” by Pope Lucius IIIrd.

Let’s not forget how much the Lord of Rimini, Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, was persecuted by the Church for having flaunted his Eleusinian-Pythagorean initiatory membership beyond what was “allowed” and for having had the Malatestian Temple built by another great initiate like Leon Battista Alberti, the first “pagan” Temple, built after more than a millennium from the Theodosian Decrees, and what’s more on the foundations of a Christian church! Not to mention the fate of Giordano Bruno and the multiple imprisonments of another great initiate like Tommaso Campanella!

As I have specified several times, the term “pagan” rarely appears in my writings and in the rare cases in which I happen to use it I always put it in quotation marks. It is, in fact, a term that I do not love and do not use willingly, since it was born, on the Christian side, with the merely derogatory intent of discrediting and denigrating an entire religious world and a set of multi-millennial Mysterical and spiritual Traditions that the new cult he attempted, with an intolerance and violence completely foreign to the ancient value system of the Mediterranean area, to destroy and eradicate.

During Middle Ages and Renaissance, it was much easier for the Church to fight its own numerous internal heresies and hunt down poor defenseless women accused of “witchcraft” rather than frontally attacking ancient religious and initiatory traditions that it had “officially” defeated and eradicated already at the end of the 4th century. Furthermore, some of these Traditions had gone underground with the tacit consent of the Church itself, if not on the basis of specific secret agreements. What mattered most for the Chair of Peter was to demonstrate in the eyes of the masses that it had won, that it had publicly defeated and eradicated its adversaries (the other cults that it began to fight since the time of Constantine) and that it had imposed its own triumphant patriarchal monolatry. And with some of these adversaries that the Church had not managed and would never be able to defeat, it was forced to come to terms: they were able to tacitly enter into an undisturbed clandestinity, provided that they did not make too much noise, that they did not attract too much attention, that did not disturb the “Pax Cristiana” and the new established order. Setting up public inquisitorial trials against non-Christian religious and initiatory realities that the Church had already “formally” defeated would have been an unthinkable proof of weakness for Christianity. It limited itself, therefore, to monitoring certain realities through its own spies and infiltrators, without realizing that the exact opposite had been happening for centuries: it was the mystery orders that infiltrated the Church, up to the highest hierarchies of the clergy, coming to control entire dioceses and even left their mark on the architecture of sacred buildings, abbeys, cathedrals and many pictorial and sculptural works of sacred art. Prudence and circumspection were a must. The initiated Eleusinians, Orphics, Pythagoreans, Isians and the followers of Hermeticism continually resorted to dissimulation, allegory, occult symbolism, ad hoc inserting dual aspects into their literary, artistic and architectural creations. meanings intended for two different interpretations: a profane, immediate, obvious one, intended for the common people, and an initiatory, hidden, hidden one, intended exclusively for those who were able to understand the secret language of the symbols.

The depiction of the Virgin Mary was therefore often used to actually symbolize the Titan Goddess Demeter, also in her senses of “Mother Earth” and universal emblem of the Sacred Feminine (no more and no less than the Cathars and the Templars did, which under the iconographic guise of the “Mother of Christ” actually depicted and venerated Magdalene). And, on the basis of a certain syncretistic practice which had already begun since late antiquity, it was not uncommon that, under the guise of the Madonna, there was a desire to represent in pictorial and sculptural works a female divinity who simultaneously covered the characteristics not only of Demeter, but also of his daughter Kore-Persephone, of Leto/Latona, of Artemis, of Venus-Aphrodite or of the Egyptian Isis.

The perpetuation and the handing down of the Mystery Tradition through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance was not always a linear and obstacle-free path. Furthermore, it would be naive and utopian to even think so. If it was, in a certain way, rather organic and direct within the two main strands of transmission, the Eleusinian Mother and the Pythagorean, also largely in the context of them, but above all in the context of “minor” or derived from them, this path often took on the characteristics of an immense fragmented mosaic, the pieces of which have never been seen, neither by profane historians (most of whom would not even understand what we are talking about), nor by the exponents of the individual initiatory realities, replaced in their correct overall vision. It is also attested that many “minor” strands (a term that is certainly improper, but necessary for the purposes of understanding) that have survived to this day have jealously closed in on themselves, jealous guardians of their fragments of truth, of their fragments of the columns of the Temple (let me use the latomistic metaphor) and of their partial sources, obstinately and determinedly avoiding any contact and any comparison with realities that are their sisters.

While the writer possesses a good part of the pieces of the mosaic inherent to the handing down and the perpetuation of his own specific initiatory tradition, the Eleusinian tradition of the Mother Rite, I recognize in all humility, despite decades of studies and research, that I only possess a few fragmentary pieces regarding the karst path through which the “Daughter” Rites of Eleusinity have reached our times, primarily the Samotracian and the Orphic. And the same applies to realities which, despite belonging to the Tradition and the line of transmission of the Mother Eleusinity, were separated from the diaspora and continued their path in isolation.

To better understand the hidden meaning and the exquisitely initiatory role of most of the “Platonic” Academies that arose and prospered in Italy between the 15th century and the advent of the Counter-Reformation, it is first necessary to focus attention on some fundamental aspects of Platonism. For Plato, the lowest degree of Knowledge was εικασία eikasía (conjecture, appearance), followed by πίστη pistis (belief). Both degrees, in the Platonic conception, belong to individuals who are not logically discriminating, not intuitive and essentially dominated by the senses and δόξα doxa (opinion). To escape the world of opinion (always changing and, as the word itself says, questionable), it is necessary to ascend to that of επιστήµη epistemi (science, knowledge).

Plato, in his Symposium, writes that it would be truly beautiful if Wisdom were able to flow from the fullest to the emptiest of us, when we come into contact with each other, like water flowing into cups through a wool thread from the fullest one to the emptiest one. But the great Athenian philosopher knew well that unfortunately this is not the case. Wisdom, in fact, is not transmitted between human beings like a fluid. Like an Initiation, wisdom learning is a personal experience that can only be lived. It is not possible to mechanically transfer it from one individual to another. As Moreno Neri rightly observed in one of his articles, great internal motivation is needed, individual effort combined with an inexhaustible passion for dialogue between person and person, and the initiation of maieutic communication through the tight dialectical method taught to us by the greatest Philosophers who, as I explained in my essay “In the Penetrations of the Temple: The Relationship between Mystery Tradition and Philosophy” were also and above all great initiates. But what if one is not “pregnant”, that is, if one is spiritually empty? If in the worst distortion and in the lowest trivialization any shred of intellectual or existential honesty is missing, if a fragment of a question is not found, if a shred of problematicity or curiosity is not discerned, even making something emerge from the soul of the interlocutor vitality turns out to be an impossible undertaking.

Plato and Aristotle in a detail of Raffaello Sanzio’s fresco The School of Athens, 1511 (Vatican, Apostolic Palaces, Room of the Signatura)

A great initiate of antiquity, Socrates, not wrongly considered the father of Maieutics, not surprisingly called this technique of his in this way. In Ancient Greek, µαιευτική (maieutiké) means “obstetrics”, “obstetric art”, and the term derives directly from µαῖα, “mother”, “midwife”. It is a method, an approach, which, far from claiming to introduce any truth into the human soul, also intends to “extract it”. Plato, in fact, in Theaetetus, explicitly states that Socrates would have behaved like a midwife, helping others to “give birth” to the truth.

Socrates, in the Platonic dialogues, therefore speaks of Maieutics precisely because his technique is a work similar to that of the midwife. He does not launch redemption programs and does not expect to attract crowds of followers, because he is aware that Knowledge can only flow from one’s soul. Maieutics, therefore, through dialogue and dialectics, limits itself to orienting the interlocutor’s thoughts towards the truth, and represents one of the key points of initiatory learning of antiquity, and expecially of the Eleusian Mystery Tradition.

This was the heart of the teaching that Plato applied in his Academy. A teaching that the greatest protagonists of Renaissance, many of whom were initiates of the Eleusinian or Pythagorean school, certainly knew how to treasure, as they have amply demonstrated in their treatises and in their immortal works.

[1] Roberto Sestito: History of the Italian Philosophical Rite and of the Ancient and Primitive Oriental Order of Memphis and Mizraìm. Ed. Libreria Chiari, Florence 2003.

[2] Roberto Sestito: quoted work.

[3] Ibidem.

[4] Justinian Lebanus: The Occult Senate of Rome, in Ignis, Year V°, n. 2, December 1992.

[5] Roberto Sestito: quoted work.

[6] Paolo Aldo Rossi: Marsilio Ficino: from “The Christianization of Magic to the Magicization of Christianity. Article on the website https://aispes.net.

[7] Ibidem.