The Soul of the World (in Greek Ψυχὴ Κόσµου, Psychè Kósmou, also known in Latin as Anima Mundi) is a philosophical concept used by the Platonists to indicate the vitality of nature in its totality, assimilated to a single living organism. It represents the unifying principle from which individual organisms take shape, which, although each one is articulated and differentiated according to its own individual specificities, are nevertheless linked to each other by a common Universal Soul. Renaissance, under the pressure of ancient mystery and initiatory schools that survived the persecutions of the Church for centuries, attempted to reconnect humanity with this Universal Soul.

As I have repeatedly highlighted in my essays and in the context of more than thirty years of research, the true history of Renaissance has yet to be fully written, and is far from having been truly understood and investigated. Despite the thousands of international publications – which are constantly increasing – and a growing renewed interest from the media in one of the most interesting and intellectually stimulating eras in human history, we can safely say that there is no more idealized, mythologized, stereotyped historical period, and at the same time misrepresented and mystified (with an impressive load of omissions and gray areas) of what characterized Italian and European events between the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the so-called Modern Age.

Ever since the French historian Jules Michelet first coined the term “Renaissance” in 1855 in reference to the “discovery of the world of Man” (even if, Giorgio Vasari already spoke of “rebirth” in his “Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors and Architects”), the diffusion of a similar definition has been great. Since the Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt, in 1860, explored and further characterized the meaning of the term, describing it as “that historical phase which, after a long period of dark decadence, gave birth to modern consciousness and humanity” [1], rivers of ink have been poured like an unstoppable flood.

Even today, a century and a half after the studies of Michelet and Burckhardt, even if giant steps have been taken to deepen and investigate multiple and important aspects of the affairs and the events of that period, both in the historiographical and historical-artistic fields (just mention the fundamental studies of Aby Warburg’s) regarding social and economic history of the 15th and 16th centuries, the image, related to the post- medieval historical period, embodied and defined by the term “Renaissance”, is still fundamentally based on the path traced by nineteenth-century historiographical studies.

Not that they aren’t important and accurate – don’t get me wrong, they’re still “gold” compared to some contemporary non-fiction literature! – but, objectively speaking, one wonders whether it still makes sense to get lost in sterile debates on hypothetical or presumed dates of the beginning or end of the Renaissance or on the equally sterile question of whether it should be considered as a moment of rupture, or vice versa as a phase of continuation compared to the Middle Ages.

Which use or benefit can offer an authentic 360-degree historical research to the debates and clashes between the theses of “continuity” and “discontinuity” if we continue to lose sight of, or not understand at all, the true nature and the deeper origins of the Renaissance?

Already in 2019, in my essay on “Camillo Agrippa”, the Quintessence of the Renaissance”[2], I focused my attention on how the Italian Renaissance is internationally known and celebrated, yet in reality not at all understood in its most intimate and real essence. If on the one hand, it can undoubtedly give pleasure and fill us with pride the fact that undisputed protagonists of this golden age and of the Italian Genius, such as Leonardo Da Vinci, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Raffaello Sanzio or Sandro Botticelli are universally known and made the object of of international exhibitions, countless studies and publications and master courses in all continents, or even immortalized in (albeit dubious and somewhat questionable) American television series, as in the case of Lorenzo the Magnificent, on the other hand we must necessarily dwell on a bitter observation: the Renaissance had many other protagonists of absolute genius, men who, with their works, theories, creations, intuitions, discoveries and inventions decisively contributed to “ferrying” the European society from the Middle Ages to the Modern Age They have been unjustly and miserably condemned to oblivion, or – at best – remembered occasionally and sporadically in encyclopedias as “minor” characters.

In this regard, I could mention many names: Matteo Palmieri, Coluccio Salutati, Luca Pacioli, Ciriaco d’Ancona, Benedetto Varchi, Camillo Agrippa, Giovanni Augurelli, Pietro Bembo, Lorenzo Valla, Bernardino Telesio, Girolamo Rarancio, Michele Marullo, Paolo Dal Pozzo Toscanelli, Marcello Palingenio Stellato, Francesco Da Meleto, Niccolò Della Luna, Cosma Raimondi, Guarino Veronese, Bartolomeo Sacchi, Giulio Pomponio Leto. And I’ll stop here, because any possible list, with even the slightest pretense of completeness, would necessarily take up an enormous number of pages.

But this is not the point. Leaving aside the question of the “Renaissance Showcase” presented for the use and consumption of hasty tourists with an indecent cultural and cognitive level – about which it is much better to keep silent – in no tourist guide, or widely popular essay, there is some space for an even simple and banal question: did the protagonists of this extraordinary season, who with their works and creations in the artistic, architectural, philosophical and literary fields have left an indelible mark of their passage, decreeing the birth of a new era, beyond the patronage that could characterize some Italian courts, act on impulse, in an isolated and random manner, or were they guided and directed by someone or something? Well, in this reflection of mine, I will try to provide an answer to this thorny question.

What the vast majority of historians ignore (or sometimes guiltily pretend to ignore) is that that great season which, starting from Italy like an unstoppable movement, spread throughout Europe, determining, in open defiance of the Holy Roman Church, of the Thomism and of the barriers of a certain pseudo-Aristotelian Scholasticism, the rediscovery of the themes of Greek and Roman classicism and that rebirth of Platonic Philosophy, Maieutics, Arts, Sciences and Consciences, conditioning in a tangible and irreversible way all the centuries to come and paving the way for the Modern Age, was anything but a result of chance. Renaissance was, beyond a natural socio-cultural evolution grafted with Humanism, mostly the implementation of a centuries-old project carried out by ancient pre-Christian mystery and initiatory orders, which entered the shadows towards the end of the 4th century with the forced Theodosian imposition of the Pauline doctrine and survived, like a silent karst river, throughout the Middle Ages, until reaffirming, with force and vigor, their presence and identity on the threshold of the 15th th century. A project that was implemented with strength and determination by the political and economic affirmation of a group of initiatory families who were closely linked to these orders and traditions. I am referring to the Medicis, the Estes, the Gonzagas, the Montefeltros, the Da Malatestas, the Da Varanos, etc, etc.

Authors such as the philosopher Julius Evola, who are still held in high regard today by certain traditionalist circles who believe they possess the authentic interpretative key to the events and history of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, have only contributed, in my opinion, to generate confusion and divert attention from a reality that many – perhaps too many, starting with the Church – are better off ignoring or keeping buried. In his essay “Revolt against the Modern World”, in the chapter entitled “Sunset of the Medieval Ecumene”, the Sicilian “Baron” wrote “verbatim”: “In Renaissance, ‘Paganity’ essentially served to develop the simple affirmation of Man, to foment an exaltation of the individual, who becomes intoxicated with the productions of an art, an erudition and a speculation devoid of any transcendent and metaphysical element”[3]. Nothing could be more false and misleading!

My friend Luca Valentini, a great scholar of the esoteric tradition, in his preface to my essay “Camillo Agrippa, the Quintessence of Renaissance”[4], addressed this vexed question with some legitimate questions: “Can Renaissance be considered an era of spiritual and archaic, rebirth? Can the traditionalist criticism be accepted according to which Renaissance Humanism did not re-propose the great teachings of classical antiquity, but all those philosophical-literary anomalies, from sophism to Democritean atomism – the Greek- Roman civilization rejected as mere deviations, establishing a modus vivendi which, philosophically, can be associated and identified with Individualism?”[5]. And again: «Did Humanism objectify itself as a mere sum of individuals, without a real ethic, without an ideality that can lead the individual beyond his own narrow spheres, towards the rediscovery of an aristocratic personality? Was it the germination of modernity, the cradle of the human, the too human “Nietzschean”, or the era of a sterile, formless imitation?”[6].

“It is undeniable – Valentini himself states in response – what is exposed by the morphology of History and of Art regarding the criticality of the formation, between the Middle Ages, Humanism and the Renaissance, of the Modern Era, but it is also indisputable as in some courts, like the Florentine one of the Medici or the Ferrarese one of the D’Este, there was trace of an underground tradition that has been perpetuated since antiquity, in which occult veins of initiatory wisdom have persisted despite the decadent trend of an entire historical era”[7].

Valentini observes that, «As the various studies on the symbolic criticality of some Renaissance pictorial or literary works testify, a double meaning is often hidden in the interpretation of each individual. They are often ambiguous, dual and opposing implications, precisely because the symbolic in itself represents a soul viaticum through which one’s internal quality is made explicit, determining transfigurations towards the some uranic skies or, at the same time, shipwrecks in indeterminate sensist materialism. It is, in fact, in the entirely Renaissance synthesis of Islamic mysticism, of Jewish and Christian cabala, of gnosis and pagan theurgy, in authors such as Pico della Mirandola, Marsilio Ficino, in the Platonic academies not only of Florence, but also in the Roman one of a Pomponio Leto, that we can find traces of a mysteriousness which has always and no less in the historical phase considered lead to the divinification of man”[8].

Francesco Del Cossa: Detail of the Fresco of the month of April, 1470 ca. (Ferrara, Palazzo Schifanoia, Salone dei Mesi)

(Ferrara, Palazzo Schifanoia, Salone dei Mesi)

I dare say that these observations are obvious and self-evident. Yet, in the vast majority of essays and historical studies on Humanism and Renaissance, with the due exceptions of talented researchers such as Edgar Wind, Diego Baratono, Claudio Piani, Monica Centanni, Anna Maria Partini, Paola Maresca, Sandra Marraghini or Bruna Rossi, the aspects of “paganity” and mysteriousness of Renaissance culture are never addressed. when they come in passing, or when they are addressed in passing, or with poorly concealed embarrassment, they are often reduced to mere folklore or a “fashion”. They are decreded in value and become bizarre curiosities or whims of bored artists or lords of the fifteenth- sixteenth century Italian courts.

This does not only happen in more strictly academic and university studies, a terrain in which the omissions regarding certain topics and research perspectives are in fact a rule imposed from above, a paradigm -, but it is also incredibly found in certain non-fiction historical literature, intended for the general public. Just to quote one example: a popular and award- winning writer like the British Paul Strathern, author of international best sellers on Renaissance and on the history of the Medici (historically well documented texts), never dedicates a single line to esoteric interests or initiatory membership of such a gentleman or such an artist.

Is it a coincidence? Of course not! If anything, we should talk about a guilty and intentional omission, about historical silence, with all the consequences of the case. When dealing with Renaissance – and any historian, even the most naïve one, knows this: it is practically impossible not to come across facts, circumstances, episodes and situations with an explicitly esoteric, mysterious- sophical and initiatory implication. As I have been explaining and documenting in my essays for several years, the question of survival and perpetuation in clandestinity, in an organic and organized form, of some strands of the pre-Christian Mystery Tradition, and of the Eleusinian one in particular, from antiquity until today through an uninterrupted thread, is absolutely not – as has been erroneously claimed by some – a mere hypothesis. These are proven and documentable historical events which have also affected other “pagan” traditions, primarily Pythagoreanism (Jean Marie Ragon, who was both a Freemason and an Eleusinian Initiate, famously documented, for example, the entire history of the perpetuation of the Pythagorean Order, from the 5th century AD until the second half of the 19th century[9]), the Orphic Eleusinity (which was also secretly handed down within some monastic orders, including the Camaldolese friars) and other realities such as the Egyptian mystery cults of Alexandrian and Ptolemaic origin (the Mysteries of Isis and Osiris and those of Serapis) and Hermeticism. These are historical events that are well known in Freemasonry, at certain levels, even if – incomprehensibly – not much is said about them even in these areas. But, at the same time, it is a question which, in a historical and academic context such as the Western one, pervaded and inevitably deeply marked by two millennia of prevailing Judeo-Christian culture, has always represented a sort of “taboo”, an insurmountable limit.

Many great historians and researchers, among whom we can include Eugenio Garin, Miles Unger, Frances Yates, Károly Kerényi, Mircea Eliade or Walter Burkert, have often found themselves faced with the truth, while glimpsing its reach. But, realizing that they could find themselves dealing with an overall picture that was not only extremely complex but also potentially explosive and dangerous – an overall picture that probably went beyond not their understanding, but the very limits of their cultural formation and their mindset – they preferred not to face it head-on. And they choose more comfortably to go around it. But – History teaches us – a mountain cannot be climbed by simply hitting its slopes with an ice ax and ignoring its summit, just as Sultan Mehmet II did not conquer the mighty walls of Constantinople by piercing small holes on their basement!

In particular, Frances Yates and Eugenio Garin managed to see this symbolic peak, but, for a whole series of reasons known only to them (but which we can legitimately guess), they deliberately chose not to climb it completely, preferring to rest on its buttresses. Yates, a talented scholar but with some interpretative limitations, rested on a buttress called

“Hermeticism”. And she settled into it so well that she ended up seeing the mythical and mythologized figure of Hermes Trismegistus and the doctrines attributed to him almost everywhere, interpreting writings, events and historical facts in a hermetic key that had nothing to do with Hermeticism ( or at least very little), or branding as “Hermetists” great figures and initiates of the past who in reality followed and practiced very different doctrines, from the Pythagorean to the Orphic, from the Isiac to the Eleusinian ones.

Eugenio Garin, on the other hand – and this can be clearly understood from his numerous books – well understood the height and dimensions of the peak he intended to climb, but he also understood its intrinsic danger. Translated into less metaphorical terms, he was able to fully understand the reality of the survival in an organic and organized form of the pre- Christian Mystery Tradition through the Middle Ages and Renaissance, but he also understood that bringing such a reality back to light could have jeopardized his university career and his reputation as an academic. A free choice, his (even if questionable) choice. In order to partially remedy, he still wanted to insert in his numerous essays on Humanism and Renaissance some fleeting but clear signals that attest to how much he really understood the issue. As if to say: “I know, but I have to keep quiet. In some Lodge or Oltretevere, someone might not like what I may write or say…“.

The authentic history of Renaissance needs to be rewritten, and the same needs to happen for many of its main protagonists: Cosimo de’ Medici , Coluccio Salutati, Marsilio Ficino, Agnolo Poliziano, Giovanni Pico Della Mirandola, Girolamo Benivieni, Pier Vettori, Leon Battista Alberti, up to Ludovico Ariosto, Niccolò Machiavelli, Amerigo Vespucci, Michelangelo Buonarroti, Sandro Botticelli, Ambrogio Traversari, Matteo Palmieri, Pomponio Leto, Giorgio Vasari, Leonardo Da Vinci, Nicolaus Copernicus and hundreds of other characters who made the history of that quite extraordinary season.

Edgar Wind, in his masterpiece “Pagan Mysteries in Renaissance”, reports a comment by Lorenzo de’ Medici on the sonnets by Pico della Mirandola, in which the classical and initiatory themes of Thanatos and Eros return with a precise and specific depth: «This same sentence seems to say that those who followed Omper, Virgil and Dante, by whom Homer sends Ulysses to the underworld, Virgil Aeneas, Dante himself to polish hell, to show that one goes to perfection along these paths”[10]. Similarly, as Vladimiro Zabugbin observes, it is in the academic teaching of Pomponius Leto that it is explained how the sacral embrace between the Egyptian deity of Serapis, represented by an ox, and Isis, which etheric Moon, represented by a cow, represented the mystic union of the antagonistic forces of the cosmos, «whose union is the origin of everything that has life” [11]. But, neither Wind nor Zabugbin have ever found the courage to explicitly state that not only were the cults and mystery rites of Isis, Osiris and Serapis widely practiced in the Italian courts of the fifteenth century, but that even, in the last years of that century, a Hierophant Catalan Isiac, Roderic Llançol de Borja, ascended to Peter’s Throne with the name of Alexander VI, just four months after the assassination of Lorenzo the Magnificent. But then, not many years later, even the Medicis (who were custodians of an Eleusinian initiatory tradition of the Orphic Rite), would have seen two of their leading exponents reign over the Church: Leo X and Clemens VII, that is Giovanni de’ Medici, son of the Magnificent’s, and Giulio de’ Medici, son of Giuliano’s, Lorenzo’s brother who was notoriously victim of the Pazzis’ Conspiracy. A conspiracy which developed not only for the well-known economic and geo-political reasons usually cited by historians, but also and above all in the context of an all-out underground war between initiatory orders.

Giorgio Gemisto Pletone, Grand Master of the Pythagorean Order, portrayed in a miniature of the proem

“Ad Magnanimum Laurentium Medicem Patriae Servatorem” by Plotinus’ Enneads,

translated into Latin by Marsilio Ficino (ms. Plut. 82.10, fol. 3r), 1490 (Florence, Laurentian Library)

The anti-Medicis hatred of certain Florentine Pythagorean circles had very ancient roots, which went well beyond the defense of republican ideals, and was expressed in all its virulence precisely in episodes such as the Pazzis’ Conspiracy: the volte-face of the Pythagorean Federico da Montefeltro (who, together with Pope Sixtus IV, was the true director of this conspiracy), the (failed) attempt to assassinate Piero the Gouty and the murders (those, however, successful) of Michele Marullo, Agnolo Poliziano, Pico della Mirandola and Lorenzo the Magnificent (who was poisoned by his physician, even though he already had one foot in the grave due to gout). There were not only economic issues at stake, as many lay historians have always maintained. At stake there were also and above all secret knowledge, the possession of certain texts and “powerful” objects and, obviously, a different approach to managing the political sphere. The Medicis, since the time of Gianni di Bicci and the chancellor of the Florentine Republic Coluccio Salutati, had embraced and embodied with conviction and determination the doctrines of the Orphic Eleusinity, which had influenced for centuries – at least until Ferdinand II – a good part of their work, both on an artistic-cultural and political level. But rest assured, no academic historian will ever dare to talk to you about this.

As I explain in the first volume of my essay “From Eleusis to Florence: the Transmission of Secret Knowledge”[12], the Italian Renaissance was not just a mere evolution of late-medieval Humanism and a “casual” and fortuitous” rediscovery of classical literature and philosophy accompanied by an extraordinary flourishing of the arts, science and culture. It was, also and above all, a clear test of strength of tenacious mystery and initiatory traditions which were able to perpetuate themselves uninterruptedly, passing unscathed through the terrible era of the persecutions of Christians against all other religions, the forced imposition of Christianity and of its absolutist-patriarchal conception of society as the only legitimate and recognized cult of the Empire and the dark ages of the Middle Ages, until re-emerging and re-exploding in all their splendor in the 15th century, with the full affirmation of humanistic principles and ideals. And among these, the Eleusian Mystery Tradition played a leading role, the most venerable and long-lived religious-philosophical-wisdom tradition of antiquity, both in its “Mother” form and in its “Daughter” derivations (Orphic, Samothracian, Pythagorean, etc.). That same Tradition which had tenaciously survived the disappearance of the Minoan Empire first and, about three centuries later, also the fall of Troy, and which from a status “in the light of the sun” had become mysterious to protect and guard itself after its transfer to Eleusis, and which was able to survive just as tenaciously, going underground at the height of the ruthless Christian persecutions of the 4th and 5th centuries, arriving almost intact, through the Middle Ages, Renaissance and the Modern Age, up to the present day.

It is a quite well framed and perfectly documentable fact, the persistence of strands of ancient mystery and pre-Christian initiatory traditions which have been able to survive and perpetuate themselves, handing down, both in elitist secret circles and in certain family circles, their wealth of traditions, values, rituals and knowledge. And the Italian Renaissance was the main and most obvious test of strength of these tenacious traditions. That extraordinary season known as the Renaissance, in fact, abundantly exudes Eleusinity, Orphism, Pythagoreanism, Hermeticism and Mysterious Tradition in the broadest and deepest sense of the term from all the various expressions that have characterized it: from Art to Literature, from Philosophy up to Architecture and Science: from the paintings of Piero Della Francesca, Raffaello Sanzio, Masolino da Panicale, to to the grandiose architectural creations of Leon Battista Alberti; from the treatises of Giorgio Gemisto Pletone, Marsilio Ficino, Giovanni Pico Della Mirandola, Matteo Palmieri, Tommaso Campanella and Giordano Bruno, to the poems and works of Michele Marullo, Torquato Tasso, Celio Calcagnini and Ludovico Ariosto; from the universal genius of Leonardo Da Vinci to the revolutionary science of Galileo Galilei or Copernicus. The main characters and supporters of the Renaissance were in fact all great Initiates, custodians of an arcane wisdom, as were the most important Italian families of that time, starting from that of the Medicis in Florence, the Gonzagas in Mantua, the Estes in Ferrara, the Sforzas in Milan, the Montefeltros in Urbino and the Da Varanos in Camerino. Families who were bilees and custodians, for countless generations, of strands of a Tradition which, crudely and derogatorily, was defined by the Church as “pagan”. But we are talking about a Tradition on which, as the great Florentine Initiate Arturo Reghini rightly underlined, the very foundations of the most authentic European and Western culture rest. A culture, the Western one, which does not have a “Judeo-Christian” soul at all, as many contemporary philosophers inappropriately like to affirm, but rather such an external armor which has been imposed on it over the centuries with violence and oppression, but which it has not succeeded – nor will it ever succeed – in permeating the depths of its core[13].

We are talking about a Tradition which, as I have had the opportunity to document in my books, has been able to infiltrate and proliferate on several occasions even within the Church itself, from the monastic orders up to the highest spheres (Basilio Bessarione docet), reaching even – and this should not be surprising – to express four Pontiffs!

It is a complex and detailed story and it is not surprising that it has been kept quiet by historians until now. A story that, as you can imagine, starts from far away, from very far away.

The Mystery Schools of the Eleusinian Mothers, surviving the Christian persecutions of the late Roman Empire and necessarily going underground to continue to exist and perpetuate themselves, have handed down and preserved over the centuries a vast heritage of ancient texts and documents which have remained completely unknown until today to the profane world. Texts and documents that were originally kept in the libraries and archives of the Mother Sanctuary of Eleusis and its priestly schools, as well as other important Temples and Sanctuaries of Eleusis in Greece, Asia Minor, Egypt, Italy and other regions of the Mediterranean, and who were saved from destruction and made safe by diligent Priests and Initiates, often at the risk of their own lives.

When the Christians took the political power in Rome, coming to firmly acquire the reins of the Empire in their hands, it is sadly known that from being persecuted they transformed into persecutors and undertook a series of growing discriminatory actions towards all other doctrines, traditions and religions which until that moment had been fully protected by the authorities and institutions of the State and had peacefully coexisted for centuries under the banner of tolerance, mutual respect and the Mos Maiorum, which represented one of the cornerstones of the Empire itself and of Roman universality. Starting from the 4th century AD, and especially after the promulgation, in 380 AD, by Theodosius and Gratian of the infamous edict of Thessalonica which imposed Christianity as the only religion, effectively prohibiting all others from continuing to exist, a large part of the then known world was thus preparing to fall into an absolutely unprecedented grip of single, exclusive and darkening thought, and to slide under a heavy cloak of intolerance and persecution. From Theodosius onwards, everything that was attributable to traditional religiosity and spirituality, from works of art to sacred architecture, from philosophy to literature, up to the simple expressions of ancient popular religiosity, was derogatorily branded as “pagan” and fact prohibited, destroyed, subjected to

censorship and damnatio memoriae.

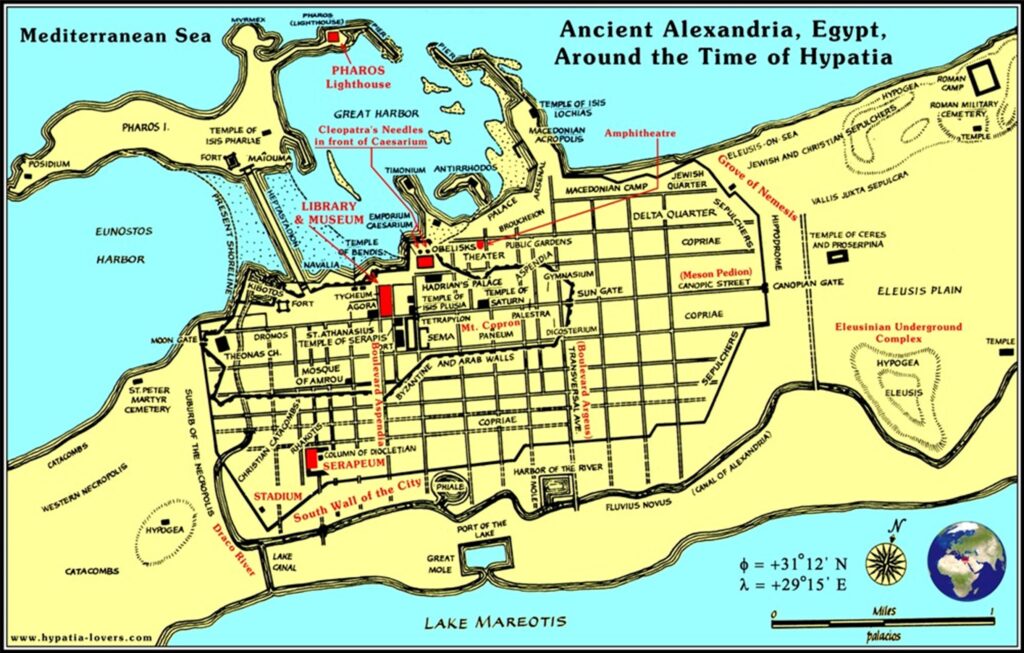

Map of Alexandria in Egypt at the time of Hypatia (4th-5th century). Note on the right the Temple of Demeter and Kore-Persephone, the so-called “Eleusinian Plain” and the large Eleusinian Underground Complex

The sad story of the destruction of the Serapeum of Alexandria and its famous Library and the assassination of Hypatia, an extraordinary figure of Eleusinian initiate and eminent philosopher and scientist, barbarically raped and massacred by Christian monks under the orders of the Alexandrian Patriarch Cyril – today venerated by Church as Saint! – is only the best- known case of a long and endless trail of blood and repression that lasted for centuries.

Everywhere, from the 4th to the 7th century, both in the East and in the West, Temples were sacked, burned and demolished, Priests martyred and libraries relentlessly set on fire. Culture, History teaches us, has always been the first victim of hatred and intolerance. The loss of the cultural and religious heritage of the Greco-Roman classicism was truly immense and incalculable at that time, and it has been estimated that only a small part of ancient literature survived and was preserved, including that of a scientific and religious nature.

Faced with the slow and inexorable collapse of a model of civilization that had guaranteed for centuries the plurality of thought and full freedom of worship and expression, and the systematic destruction of Temples, Sanctuaries and Libraries, most of the ancient religions and traditions mysterious ones, primarily the Eleusinian one (both in its Mother expression and in those derived from it, i.e. the Orphic and the Samotracian), but also the Pythagorean, the Isiac, the Mithraic and other minor ones, did not take long to understand that the path of clandestinity it would have been the only way to save what could be saved.

Of course, not all the mystery religions of antiquity managed to save their institutions and their textual and wisdom heritage in the same way, or in any case not all of them had the means, time, possibilities and resources necessary to be able to do so, entering the clandestinity in a dramatic historical moment in which it had become extremely dangerous to profess – even in private and within the home – one’s faith and religiosity. Some traditions could not withstand the impact of persecution and the violence of the Christian repressive campaign and, seeing the majority of their leaders and their priestly class arrested, imprisoned or exterminated, ended up dispersing or dissolving. Others certainly fared better at the beginning, but they still failed to perpetuate and transmit their heritage of values and knowledge for a period of time longer than that of a few generations, or in any case for no more than a few centuries, ending up running out or to be absorbed by some of the many Christian heretical currents, in particular those of the Gnosticism movement. However, the case of the Mother Eleusinians, on the one hand, and the Pythagorean Eleusinians, on the other, was different, whose survival in clandestinity is attested and documented by multiple sources. These were, in fact, the strongest and most thoroughly organized initiatory institutions of antiquity, they were certainly not without resources and important political protections and, above all, they were the most determined to preserve and safeguard their enormous wisdom and doctrinal heritage.

But how did this preservation of Knowledge and this survival of ancient mystery traditions happen in a Europe that was not only forcibly Christianized, but also pervaded by the absolutist political dominion of the Throne of Peter?

In the specific case of the Eleusian Tradition, the ecclesial institutions and the related mystery schools, after the closure, in 380 AD, of the Mother Sanctuary of Eleusis by the last Pritan of the Hierophants officially in office, Nestorius the Great, effectively moved to the interior of the Platonic Academy of Athens, founded at the same time as the closure of the Sanctuary by the Neoplatonic philosopher Plutarch of Athens, who was Nestorius’ nephew and from whom he had inherited both the knowledge and the sacral title. The Athenian academic institution represented a safe haven for the Eleusinians and for their mystery schools until the time of Justinian, and when, by decree of the latter, the Academy was suppressed, safe protections and alternative locations were already ready.

A similar path was also undertaken by the Pythagorean Order – whose secret history, as we have mentioned, is narrated to us by Jean Marie Ragon -, even if it had already distanced itself from the Mother Eleusinity for political and doctrinal reasons for some time, not recognizing the superior authority of Eleusis for several centuries and adopting a markedly “political” line.

With the entry of the Eleusinian ecclesiastical institutions into clandestinity, at the end of the 4th century AD, a clandestinity which was most likely agreed or negotiated with the Christian authorities in exchange for a formal closure of the Sanctuary of Eleusis, it was possible to safeguard and secure only the Hierà (the sacred objects of Eleusinity, among which there were real objects of “power”) and the huge treasures kept in the cells of the Temples, but also the archives and libraries of what had been for sixteen centuries the main religious and initiatory center of the entire Mediterranean area, of what was not by chance considered “the témenos of humanity“.

In fact, when not many years later, in 396 AD, Alaric’s Visigoths, at the instigation of some Christian bishops, sacked and destroyed the Sanctuary of Eleusis, they were unable to get their hands on the Hiera or the treasure, nor on the precious secret documents that they intended to steal on behalf of their instigators: everything had already been taken away and kept safe, and the barbarian hordes limited themselves to destroying the sacred statues and setting fire to the now empty buildings. Similarly, it also happened for the other main Temples and Sanctuaries of Eleusinity, whose archives and libraries were largely secured by the Priests before Christian hatred inexorably fell on these sacred buildings.

Limiting ourselves to the Sanctuary of Eleusis, which had been continuously in activity since 1216 BC. to 380 AD, therefore a truly remarkable period of time, and which had prestigious initiatory and priestly schools under its control, the mass of documents and papyri preserved in its libraries must have been decidedly impressive, certainly not inferior to those of the famous Library of Alexandria. Unfortunately, we do not have a precise estimate, but we know that there were kept, in addition to a large number of sacred and mystery texts, numerous masterpieces of ancient literature, as well as a notable repertoire of historical works, chronicles, scientific and mathematical treatises, philosophical works and geographical maps, as well as of course the meticulous archives relating to centuries and centuries of initiatory and religious activity. Unfortunately, we do not even have a precise estimate of how much of this textual material was saved in the Platonic School of Athens and how much was transferred to other places considered safer. We only know how much of this heritage has been preserved today, thanks to the diligence and dedication of numerous generations of scribes and archivists of the Eleusian Mother School, which arrived and took root in Italy in the 15th century and is still present and operating in Florence and in other cities.

But the Mother Eleusinians know very well that the numerous books and documents in their possession represent only a small part of the original collection. It is in fact attested by numerous chronicles and documents from the Renaissance period and subsequent centuries that during the dark ages of the Middle Ages, for purely security reasons, many texts were also entrusted to small groups of European families (mostly “extended” families, on the model of the phratries), descended by bloodline from the eight priestly Tribes of Eleusis. And among these, there were several of what over time became known as some of the most prestigious noble houses in Europe. Families destined to have a decisive role in the complex historical events of that time.

But certain groups of families and noble houses who, directly or indirectly, could boast descent from the eight Primary Tribes of Eleusis and who from 380 AD. onwards they had the task of transmitting, defending and preserving at all costs (alongside and in parallel with the legitimate Eleusinian ecclesial institutions that went underground) the Eleusian Mystery Tradition in the delicate and difficult phase of this clandestinity, apart from certain, limited and even risky “identity” statements, however partly concealed by symbolism and in any case never completely obvious, occurred in the Renaissance era (think of the Medicis in Florence, the Estes in Ferrara, the Guise-Lorraines in France, Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta in Rimini , the Da Varano a Camerino, Giorgio Gemisto Pletone, Piero Della Francesca, Leon Battista Alberti, etc.), have never publicly revealed themselves in this guise, and it was moreover unthinkable that they would do so. In fact, they have always had to watch their backs and protect and defend themselves on multiple fronts, both against the Catholic Church and against other opposing initiatory realities.

Jan Van Der Straet (known as Giovanni Stradano): Allegory of the Discovery of America,

1588 (Florence, Laurentian Library)

However, the perpetuation and handing down of the Mystery Tradition through the Middle Ages and the Renaissance was not always a linear and obstacle-free path. Furthermore, it would be naive and utopian to even think so. If it was, in a certain way, rather organic and direct within the two main strands of transmission, the Eleusinian Mother and the Pythagorean, also largely in the context of them, but above all in the context of “minor” or derived from them, this path often took on the characteristics of an immense fragmented mosaic, the pieces of which have never been seen, neither by profane historians (most of whom would not even understand what we are talking about), nor by the exponents of the individual initiatory realities , replaced in their correct overall vision. It is also attested that many “minor” strands (a term that is certainly improper, but necessary for the purposes of understanding) that have survived to this day have jealously closed in on themselves, jealous guardians of their fragments of truth, of their fragments of the columns of the Temple (let me use the latomistic metaphor) and of their partial sources, obstinately and determinedly avoiding any contact and any comparison with realities that are their sisters.

[1] Jacob Burckhardt: Die Kultur der Renaissance in Italien. Druck und Verlag der Schweighauser’schen Verlagsbuchhaltung, Basel 1860. Trad. it.: La civiltà del Rinascimento in Italia. Ed. Sansoni, Firenze 1943.

[2] Nicola Bizzi: Camillo Agrippa, la quintessenza del Rinascimento. Ed. Aurora Boreale, Firenze 2019.

[3] Julius Evola: Rivolta contro il mondo moderno, Edizioni Mediterranee, Tramonto dell’ecumene medievale. Le nazioni, p. 375.

[4] Nicola Bizzi: Camillo Agrippa, la quintessenza del Rinascimento. Cit.

[5] Luca Valentini: Riflessi d’antico: l’Ermetismo rinascimentale e la sacralità dei Numi pagani. Prefazione al saggio di Nicola Bizzi Camillo Agrippa, la quintessenza del Rinascimento, cit.

[6] Ibidem.

[7] Ibidem.

[8] Ibidem.

[9] Jean Marie Ragon: Notice historique sur le Pednosphes (Enfants de la Sagesse) et sur la Tabaccologie, dernier voile de la doctrine pytagoricienne. Article on magazine Monde Maçonnique n. 12 – 1859.

[10] Edgar Wind: Misteri pagani nel Rinascimento, Edizioni Adelphi, 2012.

[11] Vladimiro Zabugbin: Giulio Pomponio Letto, saggio critico, volume II, Tipografia Italo-Orientale S. Nilo, Grottaferrata 1910.

[12] Nicola Bizzi: Da Eleusi a Firenze: la trasmissione di una conoscenza segreta. Vol. I. Ed. Aurora Boreale, Firenze 2017.

[13] Arturo Reghini: Sulla Tradizione Occidentale. Ed. Aurora Boreale, Firenze 2018.