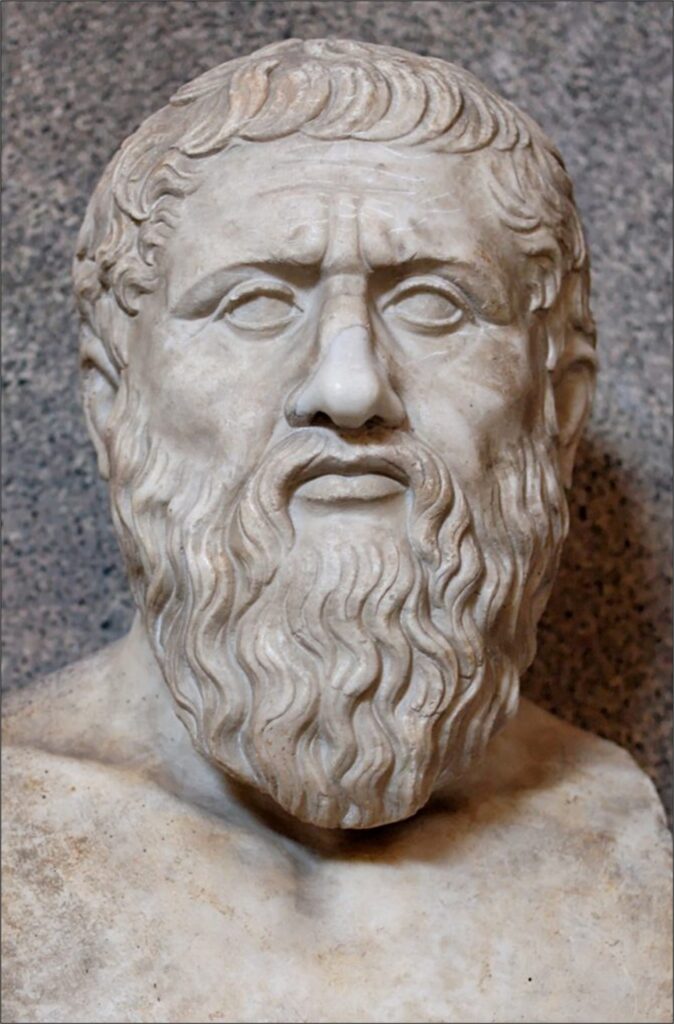

True awareness, as the most authentic Philosophy teaches us, we must – and we can – find within us. “It would be really nice, Agathon, – Plato wrote in the Symposium – if wisdom were able to flow from the fullest to the emptiest of us, when we get in touch with each other, like the water that flows in the cups through a thread of wool from the fullest to the emptiest one”. Yes, it would be nice, but we know that this is not the case. Wisdom is not transmitted as a fluid; it is not separated from whoever conceives it. It is a personal experience that can only be lived and it is not possible to transfer it ready-made, mechanically. A great inner motivation is needed, an individual effort combined with an inexhaustible passion for the dialogue between person and person. It is necessary to start a philosophical-maieutic communication through a tight dialectical method.

Socrates, Plato’s Master, taught his disciple precisely the art of Maieutics, which Plato then knew how to best use in his philosophical dialogues. But few today tend to remember that maieutiké in ancient Greek literally means “obstetrics”. This method, in fact, in Socrates’ intentions, intended to embody an action analogous to that of the midwife. In fact, he did not claim to teach anything, much less to put truths into people’s minds. He intended, if anything, to get them to give birth to truths from their minds. He didn’t launch redemption programs and didn’t claim to drag hordes of followers, because he was aware that Knowledge can only flow from the depths of ourselves, from the recesses of our soul. Maieutics, through dialogue and confrontation, limits itself to directing the thought of the interlocutor until he extrapolates the truth from within himself, that he “gives birth” to it. And this, as the great Parmenides taught us, can be possible by activating the nóos, intuition, which is the real magic word we should all equip ourselves with.

Intuition, according to Parmenides, was in fact a synonym of “being”: “… the same thing, intuition and being”, recites a fragment. According to the teaching of this great Philosopher and Initiate of antiquity, the nóos represents the human and divine organ of perception of the continuity-unity of tò eón (and in fact noein originally meant intuition), because in fact it excludes the process of differentiation typical of rational thought based on the principles of identity and non-contradiction. Intuition therefore grasps the homogeneity of all things at the tò eón, because all things, as revealed to him by that Daímon who alone can cross the inscrutable door of the ways of Night and Day, are inherent in It.

Maieutics, therefore, if well associated with intuition, effectively leads us to light ourselves, to ignite that inner light that allows us to see the Truth within us, that “super-truth” that embraces truth (alétheia) and opinion ( dóxa), which allows us to distinguish between “the apparent things” that reverberate the a-létheia (literally the non-concealed reality) and the false opinions of mortals in which there is no true certainty.

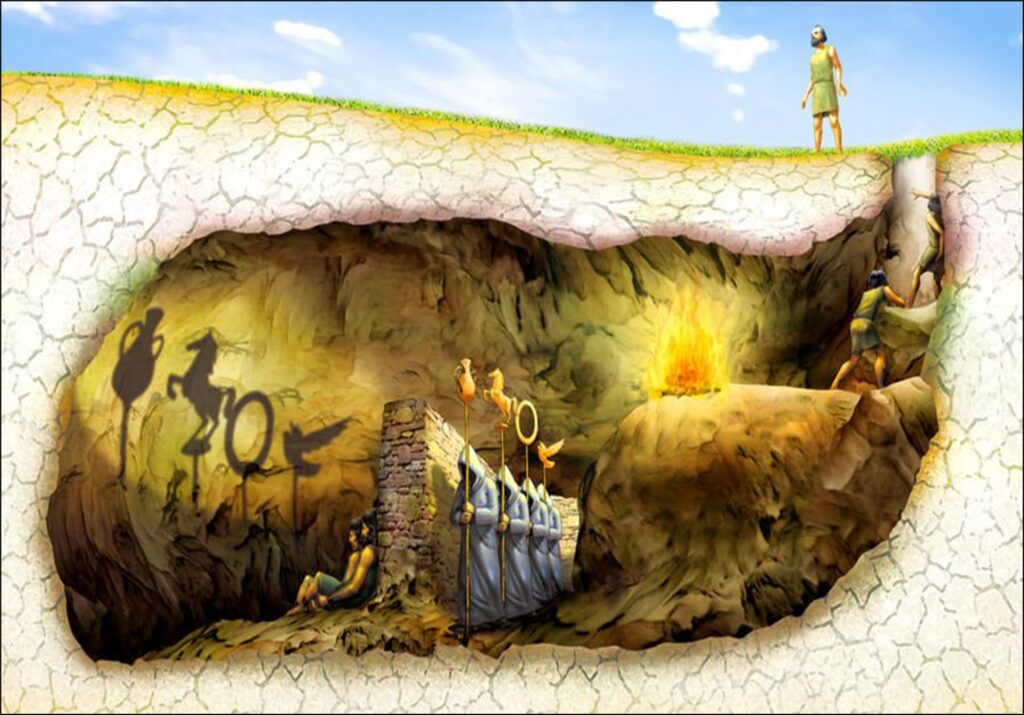

It is precisely to this double process, the famous initiatory allegory of the cave is introduced and exposed by Plato in the VIIth book of the Republic:

“Inside an underground dwelling in the shape of a cave, with the entrance however open to the light and as wide as its entire width, imagine to see men who are held captive there since childhood, bound by chains that lock their legs and necks, so much so that they cannot move and have to look only forward, unable to turn their heads due to the chain. Behind them a fire shines in the distance, between the fire and the prisoners runs a raised road. Along this, imagine to see a low wall, like those tarpaulins that puppeteers place in front of people to show the puppets above them. (…)

Imagine to see men carrying objects of all sorts protruding from the edge along the low wall, statues and other stone and wooden figures, worked in any way. And, as it is natural, some bearers speak, others are silent. (…) They look like us! Do you believe that such people can see, first of all of themselves and their companions, nothing but the shadows cast by the fire on the wall of the cave in front of them? And how can they, if they are forced to keep their head motionless for life? And for the transported items is not the same? If those prisoners could converse with each other, don’t you think they would think of calling their visions real objects?”[1]

Starting from this preamble, Plato, using his Master Socrates as narrator in an imaginary dialogue with his brother Glaucon, develops and exposes not only one of the most important philosophical metaphors of Western thought, but also one of the greatest initiatory secrets.

As we have seen, the prisoners, that Plato imagines inside the cave, have not only been there since childhood (or from birth), but find themselves having their limbs, head and neck immobilized, so that their eyes can always look in one direction only, that of the wall that is placed in front of them. Along the causeway that Plato imagines running between the prisoners and a fire placed behind them, some men (these, mind you, are free to move), are continuously carrying objects of various shapes and sizes, sometimes talking to each other, others remaining silent. The shapes of these transported objects project their shadows on the wall towards which the gazes of the prisoners are directed and, when the transporters talk to each other, they are induced to think, due to the echo that amplifies in the cave, that the voices are emitted by those same shadows that they see passing on the wall, on that barrier that separates them from the truth, from awareness. If, in fact, an external character, free to move at will, could have a complete idea of the situation, the prisoners, unaware of what is really happening behind them and around them, are led to interpret the “talking shadows” projected in front to them as real subjects.

Continuing with his dialogue, Plato hypothesizes that a prisoner is freed from his chains and is forced to stand, facing the exit of the cave. Initially his eyes would be dazzled by the sunlight, to the point of causing him pain and shock. Furthermore, those shapes carried by men along the low wall would seem to him less “real” than the shadows to which he has always been accustomed, to the point that, even if those objects were shown up close in their real appearance and the source of light, the prisoner would still remain doubtful and, suffering and feeling annoyed by staring both at the fire and at the external sunlight, Plato imagines that he would prefer to turn back to the shadows.

Wisdom is not transmitted as a fluid; it is not separated from whoever conceives it. It is a personal experience that can only be lived and it is not possible to transfer it ready-made, mechanically. A great inner motivation is needed, an individual effort combined with an inexhaustible passion for the dialogue between person and person. It is necessary to start a philosophical-maieutic communication through a tight dialectical method.

Similarly, according to Plato, if the unfortunate prisoner were forced to leave the cave and were exposed to direct sunlight, he would be blinded, he would feel terror, or at least a strong sense of unease, and he would get irritated at having been dragged away by force. from that one place he knew and where he placed (or thought he placed) all his certainties and certainties: his illusory comfort zone. However, assuming that the prisoner, driven by curiosity or by a natural instinct, a natural propensity for knowledge, takes courage and decides to adapt to the new situation, he would initially have only a confused picture of things and will barely be able to distinguish only the shadows of people around him or their reflections in the water. Only over time he could being able to cope with the light and gaze at the real shape of objects and people. Subsequently, he could, at night, turn his gaze to the sky, managing to admire the celestial bodies with greater ease than during the day. Finally, the freed prisoner would be able to turn his gaze directly to the Sun, instead of to its reflection projected on the water, and would understand that

“He is the one that produces the seasons and the years, and that governs all things of the visible world and it is the cause of everything he and his companions were seeing”[2].

Realizing the situation, finally opening his eyes to the reality of things, the now freed prisoner would undoubtedly like to return to the cave to free his companions and to make them share his liberation, his awareness. In fact, he is happy with the change and feels a strong sense of pity and empathy towards his similar ones still segregated in the cave. However, he realizes that convincing the other prisoners to be released will not be easy. Having to get his eyes used to the semi-dark again, he would need time before being able to see clearly even in the depths of the cave, and during this period he would certainly become the object of ridicule by the prisoners:

“Wouldn’t he then be the object of laughter? And wouldn’t it be said of him that from his ascent he comes back with ruined eyes and that it’s not even worth trying to go up?”[3].

Indeed, Plato continues, his work of convincing or his attempt to free the other prisoners to bring them towards the light, could even push them to kill him.

Plato’s Cave, in a painting by the Flemish School, XVIth century (Douai, Musee’ de la Chartreuse)

According to the Philosopher, humanity can be well assimilated to those prisoners segregated at the bottom of the cave and the world, knowable or understandable by men, with the limited use of their sight can well be comparable to that dark prison. The ascent and contemplation of the higher world, which would be within reach, as well as the full awareness of it which can be reached with the light of Initiation, however, is not coveted and sought after by all, as this exemplary Platonic dialogue demonstrates. And whoever acquires it, like him, inevitably sees the world with different eyes, having understood his real nature, is often in turn seen by his own kind as “different”, and distrust often turns into open hostility if an Initiate tries to direct his fellow men towards the light of Initiation and Awareness.

In the vast majority of human beings, darkened by millennia of counter-initiatory slavery, the mere thought of a rising to the superior world generates incomprehension, when not even fear and dismay, because deep down they feel happy and delude themselves that they are protected in the daily darkness of their cave, while their eyes are deceived by confused shadows that the “guardians” project on the white wall of their minds. In fact, it is much easier not to ask questions and to live one’s daily Matrix with illusory serenity.

Depiction of the allegory of Plato’s Cave

If the great Athenian Philosopher and Initiate were to return to live among us today, besides being certainly taken by the deepest bewilderment at the enormous social, moral and religious involution that he would find himself having to face, I like to think that he would be prompted to write a new dialogue and to center it on an experiment conducted in 1966 by the American scientist Gordon Stephenson of the Department of Zoology of the University of Wisconsin, US. In this experiment on the study of animal behavior, five Rhesus monkeys (a macaque of Asian origin) were placed inside a cage with a ladder on top of which was a bunch of bananas. At the sight of these, one of the monkeys climbed up the ladder to reach them, but as soon as he did so, the experimenter splashed cold water on it. The same fate then befell the other four monkeys. The cold-water deterrent only managed to inhibit the innate behavior of the macaques for a time, and the creatures soon rekindled the desire to eat the bananas placed at the top of the ladder. Another of the monkeys, in fact, attempted to climb the ladder, but was promptly driven back by the experimenter with a powerful jet of cold water. And so it was repeated, until there was an unexpected twist: when one of the monkeys tried to climb up to get the bananas, the others blocked her, beating her up. From that moment on, the five monkeys never tried to reach the bunch of bananas again.

The experiment continued entering a second phase: a new macaque was introduced into the cage in place of one of the original five. As soon as the newly arrived monkey noticed the bananas and tried to reach them, the others, mindful of the outcome of their previous attempts, forced it down the ladder and beat it. In the end, the newcomer too gave up eating bananas, and it did it without having the experience of frozen water, therefore without knowing why it couldn’t do it.

At this point in the experiment, one of the original four remaining monkeys was replaced. The new group was thus composed of the three initial monkeys, who knew why they should not try to take the bananas, a monkey who had learned to give up bananas due to the violent reaction of his companions, and a new monkey unaware of All. As expected, the newcomer attempted to reach for the bananas, but its companions promptly prevented it, even the one that hadn’t experienced icy water.

The experiment came to a close with the progressive replacement of all five original monkeys, until five new monkeys remained in the cage and were never sprayed with water. And when even the newest of these tried to reach the bananas, all the others violently prevented it, even if none of them was aware of the initial reason for the ban.

In summary, beyond mere zoological experimentation, this test by Gordon Stephenson teaches us that the animal world is only a faithful mirror of the human one, and that when a dogmatically imposed rule (the example obviously also includes religious dogmas) is handed down from one generation to the next, we get to the point where successive generations stop asking questions and passively adapt to the custom or social or religious belief, however absurd, illogical or tyrannical it may be. And it is in this way, if we think about it, that patriarchal culture, the Olympian religion, the Dionysian religion, the Amarnian monotheistic blasphemy of Amenophis IV, also known as Akhenaten, and, in the wake of the latter, were able to triumph and establish themselves, as well as Judaism, Christianity and Islam. They were all operations of a counter-initiatory nature aimed at social control and the impediment of a real elevation of the human race. Elevation that is greatly feared by the controllers and managers of the “matrix”, always on the alert to prevent (yesterday with the destruction of the Temples, Libraries and with the fires of the Inquisition, today with only apparently more “soft” methods) men from asking questions, and to ensure that they do not try to leave the cave or reach the

bunch of bananas inside their cage, in the same way that Adam and Eve were told by Yahweh not to eat the forbidden fruit of the Tree of Knowledge.

Two specimens of Rheus macaque, the monkeys used by scientist Gordon Stephenson for his famous experiment

I used this long preamble, in which I mentioned and compared, thus inviting the reader to careful reflection, Plato’s Cave allegory and Gordon Stephenson’s experiment, with the precise aim of focusing the attention on the relationship between Philosophy and Initiatory Knowledge, or, if you prefer, between Philosophy and Mysteric Tradition (and, consequently, between Philosophy and Awareness).

In the classical world and in pre-Christian antiquity, man was closer to the Gods and, at the same time – in a real exchange and union – the Gods were closer to man. And it was precisely from the Gods that men had received precise teachings, rules and doctrines and the answers to the greatest questions that humanity, since its exit from the caves, had begun to ask itself: Who are we? Where do we come from? Where do we go?

The term Philosophy (Φιλοσοφία), which in ancient Greek is composed of φιλεῖν (phileîn), “to love”, and σοφία (sophía), “wisdom”, literally means “love for wisdom”.

Modern dictionaries and encyclopaedias unanimously define Philosophy as a discipline and at the same time a field of study that asks questions and reflections on the world and on man, investigates the meaning of being and human existence, attempts to define nature and deals with the limits and possibilities of knowledge. But, as Marco Della Luna explains in Farsi Luce (Becoming Light), even before being a speculative investigation, Philosophy was a discipline capable of assuming also the characteristics of the conduction of a certain “way of life”, for example in the concrete application of the principles deduced through reflection and thought. And in this form it arises, its origins and foundations are placed, precisely in the Ancient Greece. But what made it difficult to formulate an univocal definition of Philosophy was the disagreement (still far from resolved today) between its protagonists and creators (the Philosophers) on the very object of this discipline. A false problem, this, because, if we go to the origins, the most ancient Philosophers did not place a clear line of demarcation between Philo-Sophia and Sacred Knowledge. And, as Victor Magnien rightly pointed out, “Greek Philosophy derives from the Mysteries, at least according to the opinion of the Greeks themselves”[4].

The simple translation from the Greek term (“love for wisdom”) would certainly not be sufficient in itself to give an idea of what Philosophy was and how Philosophy was understood and perceived in the ancient Hellenic world also because the meaning that the term could cover in a cultural context, that of classical antiquity, in which – as we have said – man was closer to the Gods and the Gods were closer to man, it distances itself enormously from the meanings and interpretations that were given to Philosophy in successive periods. From the Middle Ages to the Modern Age, the meanings and interpretations were characterized by completely different socio-economic and cultural-religious ambits.

But Greek Philosophy, whether we understand it as Sacred Knowledge and love for Divine Wisdom, or as a school of life and training ground for reflection, meditation, introspection and elevation, unlike species now extinct such as Homo Erectus or Homo Neanderthalensis, is anything but a thing of the past. It is still alive and pulsating today and, despite the heavy and undeniable social conditioning due to two thousand years of Christianity that have altered part of its nature and intrinsic message, it continues to form the very basis of our mindset and our cultural baggage.

Giorgio Giacometti, in one of his essays states that:

“In this we are aided by the same ancient texts which, in order to help concentration, pass from point of view to point of view (hence the appearance in them of contradiction and eclecticism)” and that “to this assistance we must add that of modern texts and teachers who provide us with the key for reading and meditating on these writings”[5].

But it is, if anything, from my point of view, the exact opposite. No author, philologist or self-styled modern “philosopher” will ever be able to provide us with the correct interpretations of the ancient Philo-Sophia, and in particular of the Platonic and Neoplatonic ones. Unless one is satisfied with the more external aspects (of the envelope, we could say), these interpretations can be reached in only two ways: through a mysterious Initiation and the relative gradual process of elevation/learning under the attentive guidance of a Mystagogo, or, in a profane way (and therefore necessarily incomplete or partial), through a prolonged and tiring careful reading of the texts of the Masters of the past, accompanied by a preparatory but indispensable cathartic stripping of any preconceived prejudice dictated by social conditioning – cultural and religious of the contemporary world.

In the vast majority of human beings, darkened by millennia of counter-initiatory slavery, the mere thought of a rising to the superior world generates incomprehension, when not even fear and dismay, because deep down they feel happy and delude themselves that they are protected in the daily darkness of their cave, while their eyes are deceived by confused shadows that the “guardians” project on the white wall of their minds. In fact, it is much easier not to ask questions and to live one’s daily Matrix with illusory serenity.

Giacometti, referring to the studies of the French philosopher and theologian Pierre Hadot – and in particular to the latter’s essay entitled “Spiritual Exercises and Ancient Philosophy[6] –– highlights a lot, as we have seen, the role of Philosophy as ασκησις, i.e. as exercise or meditation. In fact, it reminds us how Hadot, starting from the consideration of how much ancient Philosophy interpreted itself as an exercise, has come to understand how much of the ancient Tradition continues to live in us, mostly unconsciously (as power or latency) and how much it can speak to the discomfort of contemporary man certainly more and better than other Traditions, including the Christian and the Eastern ones.

From this point of view, on the basis of Hadot’s studies, Philosophy presents itself above all as the art of living, or as an art of life and death, or, if we want to be even more precise, as an art of knowing how to live and knowing how to die. And it is certainly no coincidence that such a definition is par excellence the same as that of the Mystery Tradition, and of the Eleusinian Tradition in particular, as I explain in various essays of mine.

Plato

Already in 1928, the well-known Dutch theosophist and esotericist Johannes Jacobus Van der Leeuw, in his famous essay “The Conquest of Illusion”, reminded us how Philosophy must be understood, above all, as a search for life and that it is more than love for wisdom, unless that we do not mean by wisdom anything other than knowledge. According to Van der Leeuw, wisdom itself is knowledge and experience, and therefore it is life. And the search for wisdom must therefore also be understood as a search for life. But true Philosophy must not be limited to being a mere intellectual solution to problems. In Plato’s words, Philosophy is born out of wonder, and the true Philosopher is the one who continues to marvel at life, who never ceases to do so, not the one who is certain that he has solved what lies beyond any solution. It is profoundly true, then, as Van der Leeuw teaches us, that until we are able to see the wonders of life around us, unless we see ourselves as enveloped in a mystery that defies our daring exploration, we are not yet on the planet. authentic path of Philosophy.

As Van der Leeuw always explains to us, the unawakened man knows only the facts, he knows no mysteries; for him things are self-explanatory; the world exists, what else is there to know?

But this is an animal way of seeing; to a bovine mind grazing can be good or bad, and there is no need for explanation. And therefore, the unawakened man is satisfied with the facts of existence: the environment that surrounds him, food, work, family and friends are so many “facts” that surround him, pleasant or unpleasant facts, but which for him they never seem to need to be explained. Talking to him about a mystery hidden in his life and in his world might seem vain and would make no sense; he lives, and the mere fact of living is enough for him. Death and life themselves may for a moment give him a sense of anxiety or joy, but even then they do not arouse any curiosity in him: they are basically familiar and habitual things for him. And it is precisely this apparent familiarity with life that conceals its the mystery to the animal mind.

The unawakened man, so admirably described to us by Van der Leeuw, unfortunately represents today, unlike in antiquity – when, as we said, in a real exchange and union man was closer to the Gods and the Gods closer to the man and much higher was the level of awareness – more the rule than the exception. A large part of humanity today can be assimilated to the protagonists of the allegory of the cave explained to us by Plato in the Republic and which we revisited at the beginning of this article. And Philosophy, the authentic Philo-Sophia, can, today more than ever, – unlike the prevailing monotheistic religions founded on dogmatism and the logic of “carrot and stick” – represent for many of these men a ray of light capable to pierce the darkness in which they are wrapped and thus contribute to their awakening (however traumatic it may be) and to their journey on the path of Awareness.

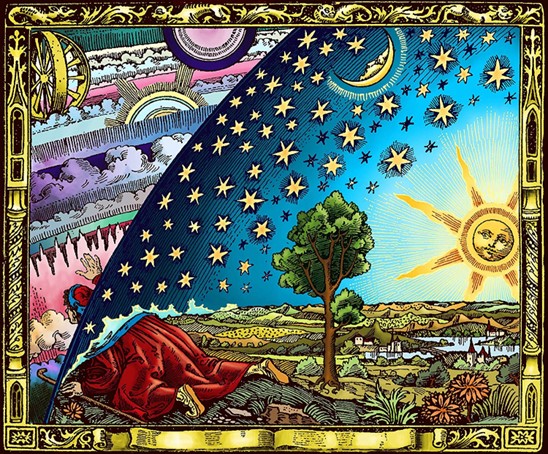

Illustration from Camille Flammarion’s book” L’atmosphère: météorologie populaire”(1888)

[1] Platone: Republic, book VII°.

[2] Ibidem.

[3] Ibidem.

[4] Victor Magnien: I Misteri di Eleusi. Ed. di Ar, Padova 1996.

[5] Giorgio Giacometti: Meditate on Plotinus. Essay available online at www.esonet.org. in the Traditional Studies section.

[6] Pierre Hadot: Spiritual Exercises and Ancient Philosophy. Ed. Einaudi, Turin 2005.