Much has been written and theorized about the mystery cults of Mediterranean antiquity. There is a vast number of studies and essays signed by the most authoritative anthropologists and historians of religions in this regard, but we must underline how the guidelines of the majority of these works are influenced by two substantial limitations. The first is constituted, despite the abundance of classical Greek and Latin sources on religious matters, by the fact that ancient authors and chroniclers such as Herodotus, Pausanias, Plutarch, Diodorus Siculus and Polybius, while addressing the interpretation of myths and doctrines religious, they never go into detail about the rituals, contents and initiatory knowledge when speaking of mystery cults. And if they sporadically do so, they still maintain an attitude of closure and confidentiality on certain issues which, in the profane eyes of our contemporaries, could even appear “silenced”. Instead, it is an obvious attitude of respect, derived above all from their adherence to the rule and vow of silence. The majority of certain authors, in fact, had personally received a mysterious initiation (and in some cases more than one), and were therefore well aware of the limes, the boundary line beyond which it was not licit to go when writing about the Gods. “On these Mysteries – Herodotus writes – which I know without exception, let my mouth observe a religious silence”[1]. And certain other authors, such as Plato, Plotinus, Proclus, Iamblichus, Virgil and the Flavian Emperor Julian himself, when dealing with religious topics, did so as initiates, addressing other initiates, and therefore used a deliberately sibylline language, rich in symbols and metaphors. A language which, however, was perfectly understandable for their interlocutors, who held the correct keys of interpretation.

A Platonic letter expresses itself as such: “It is necessary to speak to you in an enigmatic form, so that, if something were to happen to the tablet, ending up in some recess of the sea or the land, the one who reads it does not understand anything»[2]. In fact, as Soranus of Ephesus confirms to us, «sacred things are revealed to consecrated men. The profane cannot deal with it before being initiated into the Sacred Rites“[3].

The second and main limitation that modern historians of religion suffer from is purely cultural. Two thousand years of Christianity and the prevailing monotheistic culture have in fact shaped the consciences and mindset of Western man to such an extent that, by addressing issues such as the spirituality and religiosity of the ancients, he is unable to fully understand how the Greeks and the Romans conceived and lived the relationship with the Transcendent and often falls into the trap of the presumed moral superiority of Christianity.

A trap which, precisely because of the acquired cultural training, both at school and family level, leads him to mistakenly consider monotheism as a natural evolution of Western spirituality and an overcoming, in a positive and qualitative sense, of ancient “myths” and ancient “superstitions” based on ignorance. A trap into which both scholars with a “secular” approach and those with a Catholic, or in any case Judeo-Christian, education and approach inexorably fall. Both the former and the latter, in fact, base their studies, research and interpretations on the denial of the existence of the Gods and on the consequent assumption that, in the context of the ancient rites, they did not really manifest themselves in the eyes of the Initiates and faithful ones.

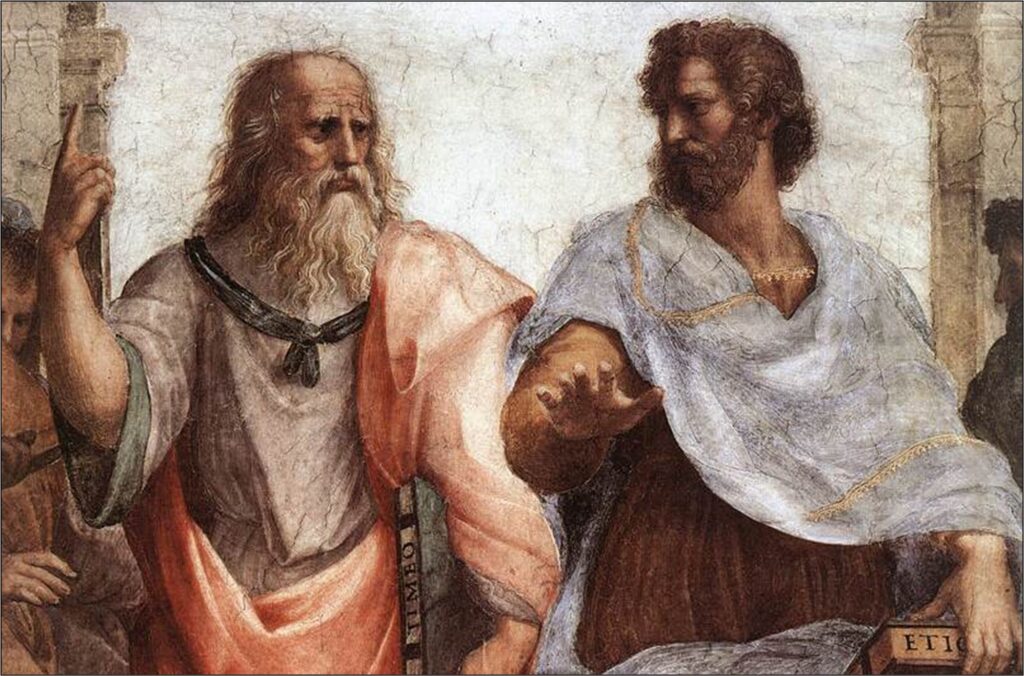

Plato and Aristotle in a detail of Raphael’s fresco

The School of Athens (Vatican, Room of the Signatura)

It is sad to note how historians and scholars, who were initiated into Freemasonry, have often fallen into this trap (with the due exceptions of great enlightened minds such as Robert Ambelain, Jean Marie Ragon or Arturo Reghini). One presumes they should have acquired, especially if they rose to high degrees, the most correct interpretations for the interpretation of the relationship with the Transcendent.

I generally disagree with the analyzes and interpretations of the mystery cults of antiquity provided to us by Walter Burkert, professor of History of Religions and Greek Philosophy at the University of Zurich, in his numerous essays, also published in Italy. But his denunciation of the survival, in the study of mystery religions, of some stereotypes and preconceptions that absolutely must be questioned, since they lead us, at best, to partial truths, if not to real misunderstandings.

The first stereotype denounced by Burkert is the one that sees mystery religions as “late”, typical of late antiquity, the imperial period or the late Hellenistic period, “when the brilliant Greek mind was giving way to the irrational”[4]. Nothing could be further from the truth, because, as we will see in the following pages, the birth of the main mystery cults is to be placed in a very archaic era, precisely between the 13th and 12th centuries BC, in that delicate moment of transition between the of the Bronze Age and that of the Iron Age, a hinge in the history of humanity which everywhere saw incredible revolutions and transformations of a political, social, religious and, last but not least, climatic and environmental nature.

The second stereotype denounced by the Swiss scholar is that according to which mystery religions are “eastern” in origin, style and spirit. It is true that regions such as Anatolia, Persia or Egypt could in the past be defined as “eastern” on the basis of a purely Europocentric point of view, and that Egypt in particular was seen by some ancient authors as the cradle of civilization and religion. But we must agree with Burkert when he writes that even the so-called “eastern” mystery cults (the Mysteries of Isis and Osiris for Egypt, those of Attis and Cybele for Anatolia and those of Mithras for Persia) «they seem to reflect the more ancient model of Eleusis»[5].

Finally, the third stereotype denounced by Burkert concerns the presumption that the birth and spread of mystery religions was dictated by a “spiritualist” turn, a fundamental change in the religious attitude of the ancient Mediterranean peoples functional or preparatory to the rise of Christianity. A stereotype that is linked to the unfounded theories of a hypothetical or presumed late-ancient “crisis” of “pagan” religiosity and which is the result of a distorted Christian-centric vision that is well connected to the cultural limitations that I discussed earlier. We can therefore agree with Burkert when he claims that “the constant use of Christianity as a reference system when it comes to mystery religions leads to distortions”[6].

By continuing to read the next chapters, you will learn to see ancient religiosity from an unexpected and surprising perspective and you will understand how mystery religions represented a never-before-reached pinnacle of religious sentiment and the relationship between Man and the Transcendent, between Cosmos and Microcosm. In religious terms, the Mysteries ensured an immediate encounter with the Divine.

It is no coincidence that a great Initiate, the Emperor Marcus Aurelius, considered the Mysteries as one of the religious forms in which we can be certain that the Gods care about us[7].

[1] Herodotus: Histories, II°, 170.

[2] Plato: Letters, 2.

[3] Soranus of Ephesus: Life of Hippocrates.

[4] Walter Burkert: Ancient Mystery Cults.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Marcus Cornelius Fronto: Letters, 3, 10.