Since the most remote times, the entire long history of the European, Mediterranean and Near Eastern religious experience has been characterized by the presence and diffusion of mystery cults They were generally characterized by a common order, by a common basic rule, consisting in the fact that the set of beliefs or foundations of the cult, of the founding myths, of the religious practices, and the true nature of the teachings and the revelatory message of the Deities should be reserved, to different degrees, for the Initiates. The initiates were admitted and entered a particular community of new men. Initiates were distinguished from the profane, from those who had not had access to the Mysteries (by choice, by impediment or for other reasons of a legal or social nature), and who as such swore a solemn oath and had the obligation to remain silent, not to reveal or profane the secret, which had to remain ineffable.

Another common characteristic of many mystery cults of antiquity, a characteristic sometimes not understood or misrepresented by modern anthropologists and historians of religions, is their nature as true revealed religions and of a salvific, messianic and eschatological character. In them, in fact, the initiatory action, and with it the acquisition and gradual understanding of the message of the Divinities, was destined to create a liberating reality offered to the individual – and, consequently, to the entire community – in response to the existential issue and problems existential concerning the connection between life and death. Through the various degrees of Initiation (which always had to be “gradual”), the adept reached the vision of the Deities and the understanding of their message. And the constant presence of the figure of a Divinity who incarnated among mortals, following a path that included birth, death and a resurrection, guaranteed the Initiates’ “liberation”, that is, the overcoming of the human state, of the individual limitation that death and resurrection of the God it symbolized; a resurrection that indicated a birth – or, better, a rebirth – beyond death and beyond this world, proving that human life does not consist of mere survival.

As I have explained in many of my essays, a fundamental mistake by modern anthropologists, from James Frazer onwards, has been the mere association of mystery cults with the cyclical nature and seasons, and consequently with the principles and concepts of fertility. In truth, it is only an exoteric and markedly popular interpretation of myth and ritual, which was presented to the profane as part of the processions and celebration of public holidays that characterized every mystery religion (events in which even those who were Initiates yet). In reality, behind certain symbols that could recall the cycles of nature and the fertility of the fields, there were important allegories and initiatory truths that were well known to the adepts, but which were completely incomprehensible to the layman and therefore easily associated to natural or “agrarian” concepts.

In fact, the mystery cults cannot be understood if we do not keep in mind that, precisely because of the presence in their systems of an initiatory path, they were characterized by a double doctrine: one for the profane and one for the Initiates.

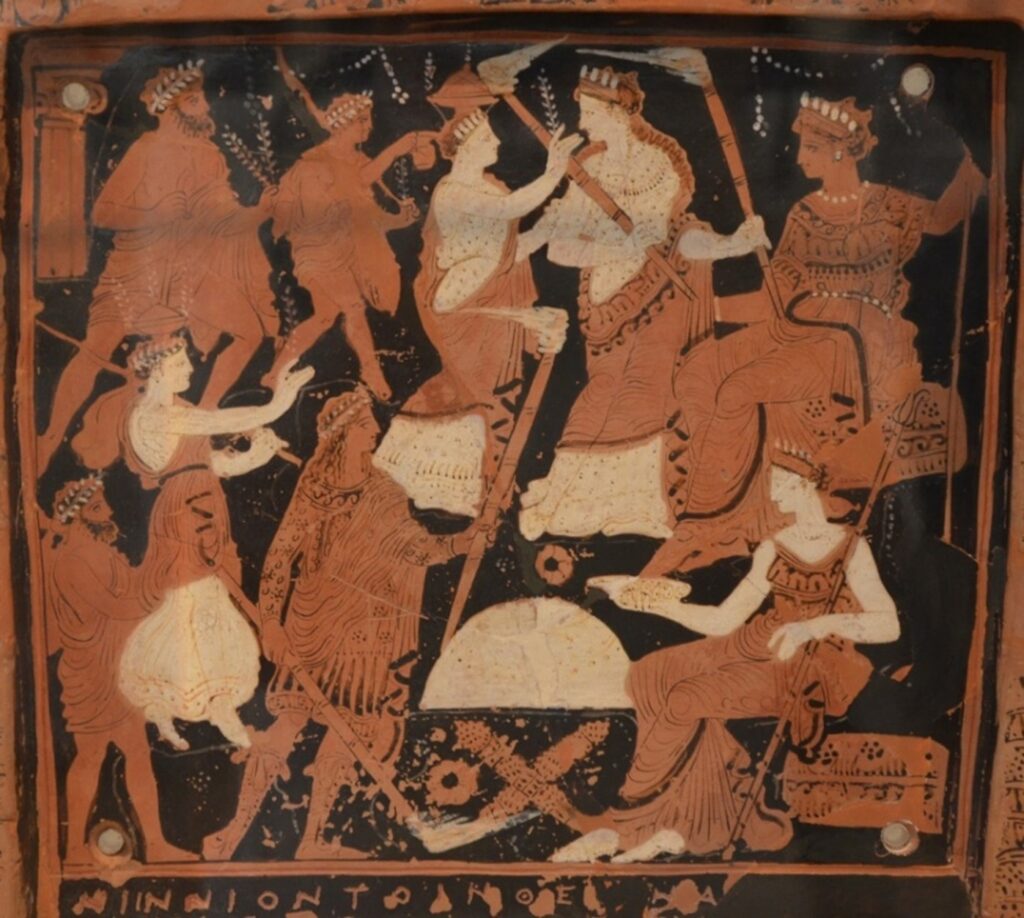

Terracotta votive plaque from Eleusis dating back to the 4th century BC, known as the Ninnion Tablet, depicting scenes from the Mysteries (Athens, National Archaeological Museum)

The Mysteries of Isis and Osiris are particularly known. They are of Egyptian origin and expecially widespread in the imperial Roman Era, the Mysteries of Adonis and Astarte, of Syriac origin, the Mysteries of Attis and Cybele, of Anatolian origin, up to the Mysteries of Aphrodite in Cyprus, to the Mysteries of the Dioscuri in Amphissa, to those of Hecate in Aegina, to the Dionysian Mysteries, to those of the Cabiri of Samothrace and those of Mithras, of Persian origin, which found an extraordinary diffusion throughout the Roman Empire, especially among the ranks of the army. But, among the various and multiple mystery cults of antiquity, none ever achieved fame, notoriety and diffusion, and at the same time secrecy and impenetrability to profane eyes, equal to that of the Eleusinian Mysteries. So much so that it has been stated by the most authoritative scholars that the very foundations of Western Culture and Tradition rest in them.

A great Initiate to the Sacred Mysteries, the rhetorician Publius Elius Aristides (117-180 AD), wrote: «Eleusis is the common Témenos of the whole Earth; among the divine things granted to men, it is the most venerable and most brilliant that exists. In what other more wonderful place have myths been sung, or have more sublime representations touched the soul? Where have we seen sights rival more happily the words heard, those stupendous scenes, accompanied by ineffable apparitions, contemplated by innumerable generations of fortunate men and women?”[1]

“The valleys of Demeter Eleusina are a common good”, proclaims a chorus of Sophocles[2]. And again, Sophocles writes: “O thrice happy are the mortals who after having contemplated these Mysteria will descend into Hades; only they will be able to live there; for everyone else everything will be suffering“[3]. “The sacrosanct Rites of Eleusis – writes Proclus – promise the initiates that they will enjoy the help of Kore once they are freed from their bodies”[4]. “Happy is he who possesses, among men, the vision of these Mysteries; he who is not initiated into the Holy Rites will not have the same fate when he remains, once dead, in the humid darkness “recites the Homeric Hymn to Demeter[5].

As the great Irish esotericist John Heron Lepper wrote, “It could be said that the existence of secret or closed societies, in which certain teachings or certain practices are transmitted to selected people and subjected to tests, responds to a very general tendency of human nature”[6]. This is undoubtedly true, but it is not a completely exhaustive explanation, as the birth and diffusion, in the ancient world, of rites of a mysterious nature, based on the principle of initiation as a prerogative for access to certain knowledge, does not it can be explained exclusively from an anthropological and sociological perspective.

Ezio D’Intra, in his introduction to the Italian edition of Victor Magnien’s work The Mysteries of Eleusis, rightly underlined that “ancient man in general, and the spiritual hierarchies of the past in particular, had access to experiences of Sacred with a frequency, a certainty and a lucidity that made them absolutely incomparable to those – maimed, occasional and fleeting, or distorted by prejudices, or artificially self-induced by strange internal gymnastics – which constitute that expanse, mostly marshy and unhealthy, of modern spiritualism“[7].

In the classical world and in pre-Christian antiquity, man was closer to the Gods and, at the same time – in a real exchange and union – the Gods were closer to man. And it was from the Gods that men had received precise teachings, rules and doctrines and the answers to the greatest questions that humanity, since its exit from the caves, had begun to ask itself: Who are we? Where do we come from? Where do we go?

By “mysterious” we mean a series of cults, religious practices and rites that developed and spread in antiquity throughout the Greek and Mediterranean world, in the ancient Near East, and later throughout the Hellenistic area and in the Roman Empire, whose roots lie in the pre-Greek cultures of the Aegean, Crete and the Anatolian coast. Cults, religious practices and rites were necessarily characterized by an initiatory path, which gave gradual access both to certain knowledge and to a consequent personal elevation, and by the most rigorous practice of silence, to which all Initiates were devoted, which did not allow anyone who did not access to teachings, revelations and everything that happened in the context of ceremonies.

The term derives from the Greek µυστήριον (mysterion), later Latinized into the form mysterium. The etymology of the word dates back to an Indo- European root (my-), which had the meaning, of onomatopoeic origin, of “to close one’s mouth” (from which, for example, the term mute derives). From this root the Greek terms µύω [myo] (“to initiate into the Mysteries”), µύησις [myesis] (“initiation”) and µύστης [mystes] (“initiated”) were derived. The verb myo was in fact used in its absolute form with the meaning of “to close the mouth” or “to close the eyes“, and in these terms the esoteric character of certain rites is well understood which, as a scholium to Aristophanes confirms, “they were called Mysteries due to the fact that the listeners had to close their mouths and not tell any of this to anyone“[8].

Participation in the ancient Mysteries, as Piero Coda underlined, normally exhibits the following characteristics:

- it demands an initiation (µύησις);

- it is expressed in precise rites;

- it implies the obligation to keep quiet about the things seen and heard during them;

- it provides participation in salvation (σωτηρία) through the joining (of the initiate) to the destiny of suffering (πάθη) and rebirth of the Divinity;

- it introduces one into a community strictly separated from the non-Initiated ones;

- it ensures immortal life[9].

As Aimé Solignac wrote, “the unifying principle of the multiple senses assumed by the words µυστήριον, µύστις, µύστης, µύστικός, µύστικώς, is the idea of a more or less immediate communication of the Divine to man and of a ‘ arcane initiation of man to the Divine, to his actions and to his very being“[10].

Eleusinian marble relief depicting Demeter, Kore and Triptolemus, 5th century BC

(Athens, National Archaeological Museum)

A phenomenon, that of mystery cults, is extremely complex and articulated and took shape in different ways, depending on the places and times, while always maintaining the common underlying characteristics that I listed earlier, the most important of which is always it was the secrecy. A characteristic which, moreover, has always been inherent since the most remote times among the ancient Mediterranean populations.

The ancient Hellenes did not conceive that anyone could participate, without distinction and without precautions, not only in the foundations of religions and spiritual doctrines, but also in Philosophy, the sciences and the arts.

The great Greek Initiate and astrologer of the 2nd century Vettius Valens, in his Anthologies, thus referred to this need for secrecy: “I ask you for an oath, Oh illustrious brother, to you and to those whom I lead, as a Mystagogue, towards the harmony of heaven. I ask you for the oath in the name of the celestial vault, of the circle with the twelve signs, of the Sun, of the Moon, of the five wandering stars that guide our entire life, for providence itself and the sacred necessity of keeping all this in secret, and of do not communicate it to the ignorant, but only to those who are worthy, who can guard and respond rightly, and confer on me, Valens, who revealed these things, an imperishable and eminent renown, recognizing that it was I who enlightened“[11].

In the Greek world and in the broader Aegean-Mediterranean context, all the arts, from that of metallurgy, understood as the fusion and processing of metals (the object of very secret, elitist and mysterious brotherhoods), to that of construction, from medicine to that of construction of ships, as Victor Magnien observed, were not accessible to everyone[12]. According to what Eustazio reports, in Rhodes there were secret arsenals, access to which was not permitted to the public and anyone who violated their doors without due authorization was put to death.

Even poets expressed themselves in a language that was not very accessible to the common man. In fact, the rhetorician and philosopher Maximus of Tire stated that “the works of poets and philosophers are all full of enigmas, and I prefer their modest respect for the truth to the overly open speech of their contemporaries; in fact, the myth deals more conveniently with those realities that human weakness cannot grasp...”[13].

According to this great philosopher and scholar of the 2nd century, poets in fact imparted the same teaching as wise men and philosophers. They “under the name of poets are actually philosophers, who use a fascinating art instead of discursively exposing the things whose knowledge is difficult for us”[14]. And, even if he wanted to exclude the poets from his ideal state, Plato wrote in his dialogue Ion that they “are simply interpreters of the Gods”[15].

Even the secret of Medicine for the ancient Greeks, and subsequently also for the Romans, was comparable to that of the Mysteries and an intimate relationship linked both Medicine, Science in general and Philosophy to religion and mystery traditions in particular. In fact, it is no coincidence that the greatest philosophers, the greatest doctors and the greatest scientists of antiquity began mystery cults, and in particular the Eleusinian Mysteries.

The secret of the Mysteries, like that of Philosophy, Science or Medicine, as Magnien observed paraphrasing the great Emperor Julian, was justified in the thought of the ancients by the fact that “nature itself loves to hide, and the truth cannot be seen without effort and without effort: therefore, those who have found this truth must not reveal it too easily to others and expose it in too explicit terms. Truth, divine by nature, and conferring great power on those who possess it, is too high for vulgar and vile men; not only do they not deserve to possess it, but moreover they could despise it if they obtained it without any effort: it must therefore be kept away from them. The truth even surpasses the faculties of ordinary men: only well-prepared and well-tested people must share it“[16].

[1] Publius Aelius Aristides: Eleusinios, t. I°, p. 256, ed. Dindorf

[2] Sophocles: Antigone: 1120.

[3] Sophocles: Fragment 719 Dindorf, 348 Didot.

[4] Proclus: On Plato’s Republic. Ed. Kroll, II°, p. 185, 10.

[5] Homeric Hymn to Demeter, 480-482.

[6] John Heron Lepper: Les Sociétés Secrètes de l’Antiquité à nos jours. Ed. Payot, Paris 1933.

[7] Victor Magnien: Les Mystères d’Eleusis. Ed. Payot, Paris 1938.

[8] Aristophanes: The Frogs (Βάτραχοι), 456.

[9] Piero Coda: The Logos and Nothingness. Ed. Città Nuova, Rome 2003.

[10] Aimé Solignac: Mystère (in Mystère et Mystique, D.S. n. 12, 1983). [11] Vetius Valens: Anthologiarum libri, IV°, 11.

[11] Vezio Valente: Anthologiarum libri, IV°, 11.

[12] Victor Magnien: Work cited

[13] Speeches by Massimo Tirio, Platonic Philosopher, translated by Signor Piero De Bardi, Count of Vernio, Florentine Academician. Ed. Appresso i Giunti, Venice 1642.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Plato: Ion, 534.

[16] Victor Magnien: Work cited.