Wu Xing (Chinese: 五行; pinyin: wǔxíng), usually translated as Five Phases or Five Agents, is a fivefold conceptual scheme used in many traditional Chinese fields of study to explain a wide array of phenomena, including cosmic cycles, the interactions between internal organs, the succession of political regimes, and the properties of herbal medicines.

The agents are Fire, Water, Wood, Metal, and Earth. The Wu Xing system has been in use since it was formulated in the second or first century BCE during the Han Dynasty. It appears in many seemingly disparate fields of early Chinese thought, including music, feng shui, alchemy, astrology, martial arts, military strategy, I Ching divination, and traditional medicine, serving as a metaphysics based on cosmic analogy.

Etymology

Wu Xing originally referred to the five major planets (Jupiter, Saturn, Mercury, Mars, Venus), which were conceived as creating five forces of earthly life. This is why the word is composed of Chinese characters meaning “five” (五; wǔ) and “moving” (行; xíng).

“Moving” is shorthand for “planets”, since the word for planets in Chinese literally translates as “moving stars” (行星; xíngxīng). Some of the Mawangdui Silk Texts (before 168 BC) also connect the wuxing to the wude (五德; wǔdé), the Five Virtues and Five Emotions. Scholars believe that various predecessors to the concept of wuxing were merged into one system with many interpretations during the Han Dynasty.

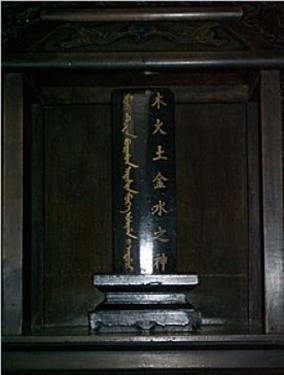

Tablet in the Temple of Heaven of Beijing, written in Chinese and Manchu, dedicated to the Gods of the Five movements. The Manchu word usiha, meaning “star”, explains that this tablet is dedicated to the five planets: Jupiter, Mars, Saturn, Venus and Mercury and the movements which they govern

Wu Xing was first translated into English as “the Five Elements”, drawing deliberate parallels with the Western idea of the four elements. This translation is still in common use among practitioners of Traditional Chinese medicine, such as in the name of Five Element acupuncture. However, this analogy is misleading. The four elements are concerned with form, substance and quantity, whereas Wu Xing are “primarily concerned with process, change, and quality”.

For example, the Wu Xing element “Wood” is more accurately thought of as the “vital essence” of trees rather than the physical substance wood. This led sinologist Nathan Sivin to propose the alternative translation “five phases” in 1987. But “phase” also fails to capture the full meaning of Wu Xing. In some contexts, the Wu Xing are indeed associated with physical substances. Historian of Chinese medicine Manfred Porkert proposed the (somewhat unwieldy) term “Evolutive Phase”. Perhaps the most widely accepted translation among modern scholars is “the five agents”, proposed by Marc Kalinowski.

The elements

The 5 elements are:

Wood (chinese 木, pinyin: mù)

Earth (chinese 土, pinyin: tǔ)

Water (chinese 水, pinyin: shuǐ)

Fire (chinese 火, pinyin: huǒ)

Metal (chinese 金, pinyin: jīn)

Fire (red) above, Metal (white) right, Water (black) below, Wood (green) left, and Earth (yellow) center

“Water consists of wetting and flowing down; fire consists in burning and in going high; wood consists of being curved or right; metal consists of bending and changing; the earth consists of provide for sowing and harvesting. That which wets and flows downward produces saltiness, what burns and rises produces bitterness; what is 3 curved or straight produces acid; what is bent and modified produces acrid; that which provides for the sowing and the harvest produces the sweet.”

(Shu-ching, The Great Plan)

The Relationships between Elements

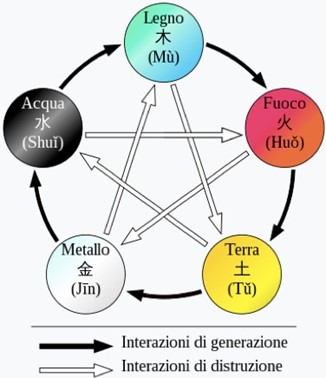

The interactions of the Wu Xing or five elements: the black arrows indicate the cycle of generation, the white ones of control or destruction. Their relationships, connections in a circle of interactions are studied mutual. The doctrine explains that there are two flows, two cycles, that of mother-child generation (ө, shēng) and that of control-inhibition grandfather-grandson (ө/Ӏ, kè).

Generation

Wood fuels the fire.

Fire causes ash, nourishing the earth.

Materials (metal) are extracted from the earth.

Metal carries water.

Water nourishes wood.

Control

Wood impoverishes the Earth.

The Earth absorbs Water.

Water puts out Fire. Fire melts Metal.

Metal breaks Wood.

The two cycles are closely connected: Water in fact extinguishes Fire, from whose ashes Earth is formed; Earth absorbs Water from which Wood of the trees is born; Wood sucks and impoverishes the Earth, which reveals the Metals inside it; the Metal of an ax cuts down the trees, whose Wood becomes ready to be burned, giving Fire; Fire melts Metal, which liquefies and transforms into Water, and the two cycles continue.

Wu Xing interactions: black arrows indicate the generation cycle, white arrows indicate control or destruction

Cycles

In traditional doctrine, the five phases are linked into two cycles of interactions: a cycle of generation or creation (生 shēng), also known as “mother-son”; and an overcoming or destructive cycle (克 kè), also known as “grandfather-grandchild.” Each of the two cycles can be analyzed forwards or backwards. There is also an “overactive” or excessive version of the destructive cycle.

Inter-Promotion Process

The generation cycle (相生 xiāngshēng) is:

Wood feeds Fire

Fire produces Earth (ash, lava)

Earth carries Metal (geological processes produce minerals)

Metal collects Water (for example water vapor condenses on metal)

Water feeds Wood (aquatic flowers, plants and other changes in the forest)

Weakening Process

The reverse generation cycle (相洩/相泄 xiāngxiè) is:

Wood depletes Water

Water rusts Metal

Metal depletes Earth (erosion, destructive extraction of minerals)

Earth suffocates Fire

Fire burns Wood (forest fires)

Inter-Regulatory Process

The destructive cycle (相克 xiāngkè) is:

Wood grips (or stabilizes) Earth (tree roots can prevent soil erosion)

Earth contains (or directs) Water (dams or river banks)

Water dampens (or regulates) Fire

Fire melts (or refines or shapes) Metal

Metal cuts (or sculpts) Wood

Exaggeration Process

The excessive destructive cycle (相乘 xiāngchéng) is:

Wood impoverishes Earth (depletion of nutrients in the soil, excessive agriculture, excessive cultivation)

Earth hinders Water (excessive destruction)

Water extinguishes Fire

Fire melts Metal (affecting its integrity)

Metal makes Wood rigid that breaks easily.

Contrasting Process

A reverse or deficient destructive cycle (相侮 xiāngwăo or 相耗 xiānghào) is:

Wood dulls Metal

Metal takes energy away from Fire (conducting heat)

Fire evaporates Water

Water muddies (or destabilizes) the Earth

Earth rots Wood (buried wood rots).

Indo-European beliefs about the fundamental types of matter

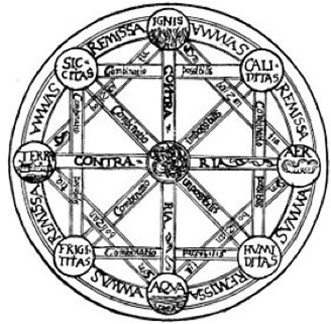

Leibniz representation of the universe resulting by the combination of Aristotle’s four elements

The classical elements typically refer to earth, water, air, fire, and (later) aether which were proposed to explain the nature and complexity of all matter in terms of simpler substances. Ancient cultures in Greece, Tibet, and India had similar lists which sometimes referred, in local languages, to “air” as “wind” and the fifth element as “void”.

The concept of five classical elements in the traditional Meitei religion (Sanamahism).

These different cultures and even individual philosophers had widely varying explanations concerning their attributes and how they related to observable phenomena as well as cosmology. Sometimes these theories overlapped with mythology and were personified in deities. Some of these interpretations included atomism (the idea of very small, indivisible portions of matter), but other interpretations considered the elements to be divisible into infinitely small pieces without changing their nature.

While the classification of the material world in ancient India, Hellenistic Egypt, and ancient Greece into Air, Earth, Fire, and Water was more philosophical, during the Middle Ages medieval scientists used practical, experimental observation to classify materials. In Europe, the ancient Greek concept, devised by Empedocles, evolved into the systematic classifications of Aristotle and Hippocrates. This evolved slightly into the medieval system, and eventually became the object of experimental verification in the 1600s, at the start of the Scientific Revolution.

Modern science does not support the classical elements to classify types of substances. Atomic theory classifies atoms into more than a hundred chemical elements such as oxygen, iron, and mercury, which may form chemical compounds and mixtures. The modern categories roughly corresponding to the classical elements are the states of matter produced under different temperatures and pressures. Solid, liquid, gas, and plasma share many attributes with the corresponding classical elements of earth, water, air, and fire, but these states describe the similar behavior of different types of atoms at similar energy levels, not the characteristic behavior of certain atoms or substances.

Hellenistic Philosophy

The ancient Greek concept of four basic elements, these being earth (γῆ gê), water (ὕδωρ hýdōr), air (ἀήρ aḗr), and fire (πῦρ pŷr), dates from pre- Socratic times and persisted throughout the Middle Ages and into the Early modern period, deeply influencing European thought and culture.

Pre-Socratic Elements

Water, Air, or Fire?

The classical elements were first proposed independently by several early Pre-Socratic philosophers. Greek philosophers had debated which substance was the arche (“first principle”), or primordial element from which everything else was made. Thales (c. 626/623 – c. 548/545 BC) believed that Water was this principle. Anaximander (c. 610 – c. 546 BC) argued that the primordial substance was not any of the known substances, but could be transformed into them, and they into each other. Anaximenes (c. 586 – c. 526 BC) favored Air, and Heraclitus (fl. c. 500 BC) championed Fire.

Fire, Earth, Air, and Water

The Sicilian Greek philosopher Empedocles (c. 450 BC) was the first to propose the four classical elements as a set: Fire, Earth, Air, and Water.He called them the four “roots” (ῥιζώµατα, rhizōmata). Empedocles also proved (at least to his own satisfaction) that Air was a separate substance by observing that a bucket inverted in Water did not become filled with Water, a pocket of Air remaining trapped inside.

Humours (Hippocrates)

According to Galen, these elements were used by Hippocrates (c. 460 – c. 370 BC) in describing the human body with an association with the four humours: yellow bile (Fire), black bile (Earth), blood (Air), and phlegm (Water). Medical care was primarily about helping the patient stay in or return to their own personal natural balanced state.

Plato

Plato (428/423 – 348/347 BC) seems to have been the first to use the term “element (στοιχεῖον, stoicheîon)” in reference to air, fire, earth, and water. The ancient Greek word for element, stoicheion (from stoicheo, “to line up”) meant “smallest division (of a sun-dial), a syllable”, as the composing unit of an alphabet it could denote a letter and the smallest unit from which a word is formed.

Aristotle

In “On the Heavens” (350 BC), Aristotle defines “element” in general:

An element, we take it, is a body into which other bodies may be analysed, present in them potentially or in actuality (which of these, is still disputable), and not itself divisible into bodies different in form. That, or something like it, is what all men in every case mean by element.

— Aristotle, On the Heavens, Book III, Chapter III

In his On Generation and Corruption, Aristotle related each of the four elements to two of the four sensible qualities:

- Fire is both hot and dry.

- Air is both hot and wet (for air is like vapor, ἀτµὶς).

- Water is both cold and wet.

- Earth is both cold and dry.

A classic diagram has one square inscribed in the other, with the corners of one being the classical elements, and the corners of the other being the properties. The opposite corner is the opposite of these properties, “hot– cold” and “dry–wet”.

Aether

Aristotle added a fifth element, Aether (αἰθήρ aither), as the quintessence, reasoning that whereas Fire, Earth, Air, and Water were earthly and corruptible, since no changes had been perceived in the heavenly regions, the stars cannot be made out of any of the four elements but must be made of a different, unchangeable, heavenly substance. It had previously been believed by pre-Socratics such as Empedocles and Anaxagoras that aether, the name applied to the material of heavenly bodies, was a form of fire. Aristotle himself did not use the term Aether for the fifth element, and strongly criticized the pre-Socratics for associating the term with Fire. He preferred a number of other terms indicating eternal movement, thus emphasizing the evidence for his discovery of a new element. These five elements have been associated since Plato’s Timaeus with the five platonic solids.

Neo-Platonism

The Neoplatonic philosopher Proclus rejected Aristotle’s theory relating the elements to the sensible qualities hot, cold, wet, and dry. He maintained that each of the elements has three properties. Fire is sharp, subtle, and mobile while its opposite, earth, is blunt, dense, and immobile; they are joined by the intermediate elements, air and water, in the following fashion:

Ermeticism

A text written in Egypt in Hellenistic or Roman times called the Kore Kosmou (“Virgin of the World”) ascribed to Hermes Trismegistus (associated with the Egyptian god Thoth), names the four elements fire, water, air, and earth. As described in this book:

“And Isis answer made: of living things, my son, some are made friends with Fire, and some with Water, some with Air, and some with Earth, and some with two or three of these, and some with all. And, on the contrary, again some are made enemies of Fire, and some of Water, some of Earth, and some of Air, and some of two of them, and some of three, and some of all. For instance, son, the locust and all flies flee Fire; the eagle and the hawk and all high-flying birds flee Water; fish, Air and Earth; the snake avoids the open Air. Whereas snakes and all creeping things love Earth; all swimming things love Water; winged things, Air, of which they are the citizens; while those that fly still higher love the Fire and have the habitat near it. Not that some of the animals as well do not love Fire; for instance salamanders, for they even have their homes in it. It is because one or another of the elements doth form their bodies’ outer envelope. Each soul, accordingly, while it is in its body is weighted and constricted by these four.”

Ancient Indial Philosophy

Hinduism

The system of five elements are found in Vedas, especially Ayurveda, the pancha mahabhuta, or “five great elements”, of Hinduism are:

bhūmi or pṛthvī (Earth),

āpas or jala (Water),

agní or tejas (Fire),

vāyu, vyāna, or vāta (Air or wind)

ākāśa, vyom, or śūnya (space or zero) or (Aether or void).

They further suggest that all of creation, including the human body, is made of these five essential elements and that upon death, the human body dissolves into these five elements of nature, thereby balancing the cycle of nature.

The five elements are associated with the five senses, and act as the gross medium for the experience of sensations. The basest element, Earth, created using all the other elements, can be perceived by all five senses—(i) hearing, (ii) touch, (iii) sight, (iv) taste, and (v) smell. The next higher element, Water, has no odor but can be heard, felt, seen and tasted. Next comes Fire, which can be heard, felt and seen. Air can be heard and felt. “Akasha” (aether) is beyond the senses of smell, taste, sight, and touch; it being accessible to the sense of hearing alone.

Buddhism

Buddhism has had a variety of thought about the five elements and their existence and relevance, some of which continue to this day.

In the Pali literature, the mahabhuta (“great elements”) or catudhatu (“four elements”) are Earth, Water, Fire and Air. In early Buddhism, the four elements are a basis for understanding suffering and for liberating oneself from suffering. The earliest Buddhist texts explain that the four primary material elements are solidity, fluidity, temperature, and mobility, characterized as Earth, Water, Fire, and Air, respectively.

The Buddha’s teaching regarding the four elements is to be understood as the base of all observation of real sensations rather than as a philosophy. The four properties are cohesion (Water), solidity or inertia (Earth), expansion or vibration (Air) and heat or energy content (Fire). He promulgated a categorization of mind and matter as composed of eight types of “kalapas” of which the four elements are primary and a secondary group of four are colour, smell, taste, and nutriment which are derivative from the four primaries.

Thanissaro Bhikkhu (1997) renders an extract of Shakyamuni Buddha’s from Pali into English thus:

“Just as a skilled butcher or his apprentice, having killed a cow, would sit at a crossroads cutting it up into pieces, the monk contemplates this very body — however it stands, however it is disposed — in terms of properties: ‘In this body there is the earth property, the liquid property, the fire property, & the wind property.”

Tibetan Buddhist medical literature speaks of the pañca mahābhūta (five elements) or “elemental properties”: earth, water, fire, wind, and space. The concept was extensively used in traditional Tibetan medicine. Tibetan Buddhist theology, tantra traditions, and “astrological texts” also spoke of them making up the “environment, [human] bodies,” and at the smallest or “subtlest” level of existence, parts of thought and the mind. Also at the subtlest level of existence, the elements exist as “pure natures represented by the five female buddhas”, Ākāśadhātviśvarī, Buddhalocanā, Mamakī, Pāṇḍarāvasinī, and Samayatārā, and these pure natures “manifest as the physical properties of earth (solidity), water (fluidity), fire (heat and light), wind (movement and energy), and” the expanse of space. These natures exist as all “qualities” that are in the physical world and take forms in it.

Post-Classical History

Alchemy

The elemental system used in medieval alchemy was developed primarily by the anonymous authors of the Arabic works attributed to Pseudo Apollonius of Tyana. This system consisted of the four classical elements of air, earth, fire, and water, in addition to a new theory called the sulphur- mercury theory of metals, which was based on two elements: sulphur, characterizing the principle of combustibility, “the stone which burns”; and mercury, characterizing the principle of metallic properties. They were seen by early alchemists as idealized expressions of irreducible components of the universe and are of larger consideration within philosophical alchemy.

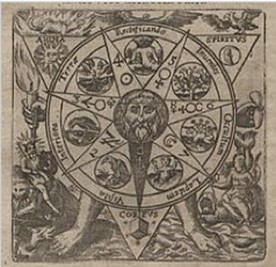

Seventeenth century alchemical emblem showing the four Classical elements in the corners of the image, alongside the tria prima on the central triangle

The three metallic principles—sulphur to flammability or combustion, mercury to volatility and stability, and salt to solidity—became the tria prima of the Swiss alchemist Paracelsus. He reasoned that Aristotle’s four element theory appeared in bodies as three principles. Paracelsus saw these principles as fundamental and justified them by recourse to the description of how wood burns in fire. Mercury included the cohesive principle, so that when it left in smoke the wood fell apart. Smoke described the volatility (the mercurial principle), the heat-giving flames described flammability (sulphur), and the remnant ash described solidity (salt).

Central Africa

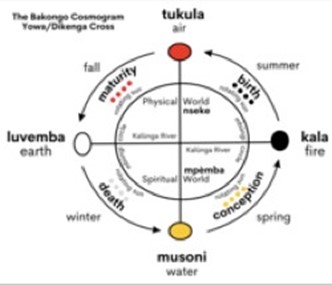

In traditional Bakongo religion, the four elements are incorporated into the Kongo cosmogram. This sacred symbol depicts the physical world (Nseke), the spiritual world of the ancestors (Mpémba), the Kalûnga line that runs between the two worlds, the sacred river (mbûngi) that began as a circular void and forms a circle around the two worlds, and the path of the sun. Each element correlates to a period in the life cycle, which the Bakongo people also equate to the four cardinal directions and seasons. According to their cosmology, all living things go through this cycle.

The Bakongo Cosmogram

Water (South) represents Musoni, the period of conception that takes place during spring.

Fire (East) represent Kala, the period of birth that takes place during summer.

Air (North) represents Tukula, the period of maturity that takes place during fall.

Earth (West) represents Luvemba, the period of death that takes place during winter.

Aether represents Mbûngi, the circular void that begot the universe.

Japan

Japanese traditions use a set of elements called the 五大 (godai, literally “five great”). These five are earth, water, fire, wind/air, and void. These came from Indian Vastu shastra philosophy and Buddhist beliefs; in addition, the classical Chinese elements (五行, Wu Xing) are also prominent in Japanese culture, especially to the influential Neo- Confucianists during the medieval Edo period.

Earth represented rocks and stability.

Water represented fluidity and adaptability.

Fire represented life and energy.

Wind represented movement and expansion.

Void or Sky/Heaven represented spirit and creative energy.

Medieval Aristotelian Philosophy

The Islamic philosophers al-Kindi, Avicenna and Fakhr al-Din al-Razi followed Aristotle in connecting the four elements with the four natures heat and cold (the active force), and dryness and moisture (the recipients).

Native American Tradition

The medicine wheel is a sacred symbol across many Indigenous American cultures that signifies Earth’s boundary and all the knowledge of the universe. It depicts the four cardinal directions, the path of the sun, the four seasons and the four sacred medicines. Each element is also represented by a color that signifies those four races of humans.

Earth (South) represents the youth cycle, summer, the Indigenous race, and cedar medicine.

Fire (East) represents the birth cycle, spring, the Asian race, and tobacco medicine.

Wind/Air (North) represents the elder cycle, winter, the European race, and sweetgrass medicine.

Water (West) represents the adulthood cycle, autumn, the African race, and sage medicine.

The medicine wheel symbol is a modern invention dating to approximately 1972, with these descriptions and associations being a later addition.

The associations with the classical elements are not grounded in traditional Indigenous teachings and the symbol has not been adopted by all Indigenous American nations.

Modern History

Chemical Element

The Aristotelian tradition and medieval alchemy eventually gave rise to modern chemistry, scientific theories and new taxonomies. By the time of Antoine Lavoisier, for example, a list of elements would no longer refer to classical elements. Some modern scientists see a parallel between the classical elements and the four states of matter: solid, liquid, gas and weakly ionized plasma.

Artus Wolffort, The Four Elements (1641)

Modern science recognizes classes of elementary particles which have no substructure (or rather, particles that are not made of other particles) and composite particles having substructure (particles made of other particles).

Western Astrology

Western astrology uses the four classical elements in connection with astrological charts and horoscopes. The twelve signs of the zodiac are divided into the four elements: Fire signs are Aries, Leo and Sagittarius, Earth signs are Taurus, Virgo and Capricorn, Air signs are Gemini, Libra and Aquarius, and Water signs are Cancer, Scorpio, and Pisces.

The “Shan Shou Da Chuan” (Occ. Han dynasty 206 BC – 24 AD) says: “… Water and Fire provide food, Wood and Metal provide prosperity, and Earth provides us with supplies…”

For the “Shang Shou” (Occ. Zhou dynasty 1000 BC) the 5 elements are: Water, Fire, Wood, Metal and Earth.

“Water flows downwards, humidifying,

Fire blazes upwards,

Wood can be bent and straightened,

Metal can be shaped and tempered,

Earth allows sowing, growth and harvest”

and goes on:

“…what bathes and descends (Water) is salty, what blazes upwards (Fire) is bitter, what can be bent and straightened (Wood) is acid, what can be shaped and tempered (Metal) is spicy, that which allows sowing and growth (Earth) is sweet…”

The four elements: the conditions for existence.

The four elements plus one: life appears, the center makes life possible, it is the place from which everything emanates and on which everything converges.

In the microcosm Man:

source of Life (direct light) is the Heart

source of Life (reflected light) is the Brain

seat of Life (metaphysical life) is the region called the solar plexus

seat of Life (physical life) is the navel.

The Heart is therefore the Center of Man, emanation of the principle of life, nucleus of immortality within us.

It is connected with all the centers of all beings in the Universe.

Man

The result of the interaction between the influences of the sky (round) on the earth (square)…

.

“…of the Five Elements, none is predominant.

Of the four seasons, none lasts eternally.

The days are sometimes long, sometimes short.

The Moon wanes and waxes…

Sun Tzu. The Art of War

Web surfing by Lorena Monguzzi

Sources:

- Wiki Engiish

- Wu Xing – The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Fjve Elements Theory, Chinese Herbs Info

- Wikimedia Commons, Classical Elements

- healthline.com

- demetra.com